This excerpt from the second volume of Jan Peterson’s trilogy on the history of Nanaimo profiles the multicultural face of the city at the turn of the 20th century. Miners from many countries lived and worked side by side and formed mutual-aid societies to provide relief during times of hardship.

Nanaimo miners had a strong sense of community, and family ties were strong. Many descendants of the first miners still worked underground and made a comfortable living for their families. They valued their British identity.

When Queen Victoria died on Jan. 22, 1901, Nanaimo city council declared an official day of mourning. The Dominion Post Office building on Front Street was draped in black, reflecting the sadness felt in the community.

However, the cultural identity of the town had changed with the arrival of the Chinese, Japanese, Norwegians, Italians, Finns, Croatians and other European workers. These newcomers gave the community a decidedly multi-cultural look; it was, in many ways, a microcosm of the future face of Canada.

The Finns, who came to Nanaimo and worked in the Western Fuel Company mines, settled around Milton Street in an area that became known as Finn Town. Others made their homes in Wellington and worked for the Wellington Colliery, while some cleared farms in the Cedar district and became farmers. The Nanaimo Finn miners built a church at the corner of Milton Street and Victoria Road, a building that still stands today.

The Wellington Finn miners founded the Kalevan Kansa Colonization Company Limited, whose sole purpose was to organize colonies and bring immigrants from Finland to B.C. They regarded the president of the company, Kurrika, as a prophet, someone who believed in the inherent goodness of man. He was described as a handsome man — tall, with a charming personality.

Kurrika and fellow Finn Matti Halminen searched up and down the coast for a location to organize a Finn colony. Malcolm Island was chosen and named Sointula — The Land of Harmony. On Nov. 27, 1901, a contract was signed with the provincial government giving the company immediate control of Malcolm Island and promising ownership after seven years if the population increased and improvements were made.

On Dec. 6, 1901, the first of the Nanaimo Finns left for Malcolm Island, where logging began almost immediately, providing lumber for building homes. Slowly, their numbers increased as more countrymen arrived from the prairies and from Finland.

Unfortunately, the colony got buried under a huge load of debt. Creditors seized timber, the Dominion Trust took possession of the sawmill, and the government took all lands in exchange for a loan to cover the colony’s debts. Dominion Trust sold all the property and forests that had come into its possession for $5 an acre. The dream of a Finnish paradise never materialized.

The first Italians to settle here in 1865 were Bartolomeo Corso, Joe Vazzo and Joe Cuffalo. Corso divided his time between fishing and farming, and occasionally did some logging. Cuffalo worked in the mines and managed to save enough money to build the Wellington Hotel in South Wellington. When this burned down, he built the Italian Hotel (Columbus Hotel) on Haliburton Street in 1885.

On Nov. 4, 1900, the Felice Cavallotti Mutual Relief Society was formed at Extension, named after a 19th-century poet and politician who was known for his efforts to bring democracy to Italy. There were 54 founding members of the society, all male. (Women were admitted to membership in 1946.) The first president was John Giovando. Other chapters of the society were soon formed in Nanaimo and Cumberland.

The society’s mission was to help Italian coal miners and their families. Since there were no social programs in existence at that time, injured miners or sick people relied on family and friends for aid until a group of miners banded together to help each other. To be eligible to join you had to be of Italian ancestry, and dues were $1 per month — the going rate for room and board at the time. The benefits in the event of an injury or sickness were $1 per day up to 100 days, then $15 per month for a further 12 months.

The communities of Nanaimo, Ladysmith and Extension were home to a number of Croatian families who worked in the mines in the district. They brought a distinctly European flavour to the communities, particularly during celebrations, with their traditional dress and music.

In 1903, the National Croatian Society, St. Nicholas Lodge, was formed in Ladysmith; it was the first Canadian branch of the society, whose origin was in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. The first meeting was held Oct. 21 in the home of William (Bill) Keserich. Eighteen members voted unanimously to elect Keserich as the first president. The society offered cultural and social activities as well as insurance protection.

The Croatian orchestra or “tamburitza,” with Jack Djuric as first musical director, staged many musical concerts in all the neighbouring communities. The 12-piece orchestra entertained at dances, churches and special events. It was most in demand during Christmas and New Year celebrations. Dressed in their national costumes, the tamburitza musicians went from house to house, singing special Christmas songs, wishing good health and happiness to households, and receiving food and gifts for their performances.

Zelimir Juricic of the Croatian community described the mood at Christmas: “There was a special bond of understanding between miners at Christmas, which transcended language and cultural boundaries. We were of different nationalities, the Croatians, the English and others, but at Christmas we all got together because coal miners, they all had the same worries and the same way of life.”

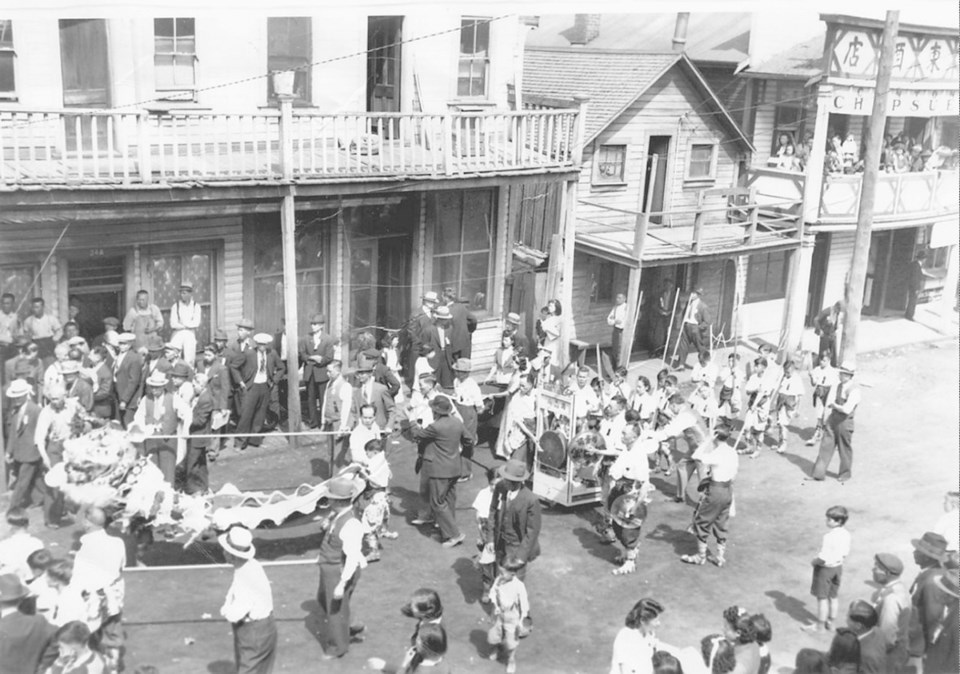

The Chinese had an active social life, often based on social connections from the homeland. There were benevolent associations that looked after the health and welfare of their members in the cities of Victoria and Vancouver. These associations had members in Nanaimo, as there were not enough Chinese in the Nanaimo area alone.

The associations, or tongs, were based on surname, dialect, district and political affiliation. Rooming houses in Nanaimo’s Chinatown housed men according to their membership in these tongs. If a man was hurt in the mines, the association made sure he was cared for. If he was seriously injured, the tongs raised money for his passage back to China.

At the turn of the century, there were 1,439 Chinese in the Nanaimo district. In addition to the city population, there were a number of small Chinese camps along the E&N Railway. Workers in these camps came into Nanaimo’s Chinatown from the mines in Extension, South Wellington, Wellington and Jingle Pot to shop or do business. They arrived by train on Saturday night, stayed over to Sunday and left on the afternoon train. On Saturday nights, Chinatown would be alive with people talking and shopping.

Social life often involved gambling. There were eight gambling houses operating at the turn of the century. During an evening, Chinese gamblers moved from house to house, playing for a period of time at each. They shared the profits and the risks among the various houses. One raid in 1904 resulted in the arrest of 18 Chinese. There had been no guards on the doors and no means of escape. It was the first raid in eight years and was to result in a crackdown on gambling.

Hub City: Nanaimo 1886-1920 © Jan Peterson 2009, Heritage House Publishing