Over a 10-year period in the mid-19th century, a little-known war waged between British and American citizens of the Pacific Northwest over ownership of the San Juan Islands. Spurred on by ambitious men, but cooled by the refusal of either country to fully intervene, the conflict would ultimately claim a Berkshire boar as its only casualty.

In 1846, Britain and the United States settled the question of how to divide the vast Oregon Country. The diplomats came to a compromise. By the Oregon Treaty of 1846, the border would follow the 49th parallel of latitude from the Rocky Mountains to the sea.

The boundary path through the middle of Juan de Fuca Strait could scarcely be disputed. But the line that joined the two was dim indeed. There were several channels separating the continent from Vancouver Island. Positioned between these channels were a cluster of islands known as the San Juans.

The treaty could be interpreted to mean the correct channel would be Rosario Strait, along the southern side of the San Juans. But it could also be Haro Strait, along the northern side of the islands, or even smaller straits between San Juan Island, the largest of the cluster, and most of the rest of the islands. Spurred on by the ambiguity, both nations claimed the San Juan Islands.

The San Juans were perhaps not as strategically or economically important as the Columbia River region, but they did overlook the strait across from Victoria and could be of military importance. Chief Factor James Douglas was convinced that the islands were rightfully British, and he did not plan to lose them to the United States through neglect.

In July of 1845, or so he claimed, Douglas sent men south to place a tablet claiming San Juan Island for Britain at the top of a low mountain on the south end of that island. Since the act took place before the Oregon Treaty of 1846 was signed, he declared, San Juan was clearly a British possession.

In 1853, Douglas established Belle Vue sheep farm on the southern end of the island and appointed Charles Griffin to run it. Lyman Cutlar, one of the disappointed goldrushers who hied to San Juan, also settled on a piece of land near Belle Vue headquarters, built a log shanty and moved in with his native companion. He built a makeshift fence that partially enclosed his garden.

Instructed not to get in their way or do anything to interfere with them, Griffin could only suffer their presence in relative silence. Early on May 15, a Berkshire boar wandered from the Belle Vue barns to the potato patch of Cutlar. He saw the hog “at his old game,” Cutlar later wrote. “I immediately became enraged … and upon the impulse of the moment seazed [sic] my rifle and shot the hog.”

He walked the two miles to Griffin’s house and offered to pay for the dead pig. Fine, said Griffin: $100 please.

The next day, three officials visited: The head of the Hudson’s Bay Company in the region, another HBC functionary and a member of the Vancouver Island Legislative Council — a nice mix of company and civil interests. The visit was possibly coincidental or might have been a result of the report of the pig shooting and the subsequent quarrel.

The three visitors went with Griffin to Cutlar’s cabin. Cutlar later wrote that the foursome threatened him, saying that if he did not pay the $100, he would be arrested and transported to Victoria for trial. Cutlar, in turn, replied that they’d better bring a posse, for he and his friends would fight any such move with whatever force was required.

Cutlar told his side of the story to American customs inspector Paul Hubbs Jr., who had been posted on San Juan Island. Hubbs, who was easily outraged, had already complained to his boss about the “intolerable and odious” monopoly exercised by the HBC on the island.

American general William Selby Harney crossed Juan de Fuca Strait aboard USS Massachusetts and arrived at San Juan Island. Harney was making a tour of settlements in the area. Harney walked through the HBC settlement to Hubbs’ house. Hubbs described the settlers’ fear of the northern natives, claiming against all truth that the HBC let them raid American settlements and kill Americans at will. Then he described the killing of the pig and the succeeding events. We are powerless here, he said to Harney. Send troops to protect us.

Much to Hubbs’ satisfaction, Captain George Pickett was ordered from his post at Fort Bellingham to San Juan Island. Massachusetts was to convey soldiers to San Juan and patrol the surrounding channels, to be ready in case of any further quarrels with the British and to prevent native raids.

Pickett landed his company of 60 men and began to make camp a stone’s throw from the HBC wharf.

There was no doubt that the landing of American troops on San Juan was a significant escalation in the battle over the island. While men on both sides of the question did call for forbearance and diplomacy, others shouted for vengeance over the perceived slight to national honour. Both sides publicly declared they would not fire the first shot, but neither would they submit tamely to a forcible takeover. The Americans declared that if the British fired the first shot, they would fight against the British until the last American soldier had been killed or captured.

Could Douglas order British troops to the island, in part to protect commercial interests? It had been done before. But Douglas needed instructions from his masters in London. Douglas sent off a request for advice, but his letter would take six weeks to get to London. A reply would take an equal six weeks to reach Victoria. He could not expect to get an answer to his questions before October.

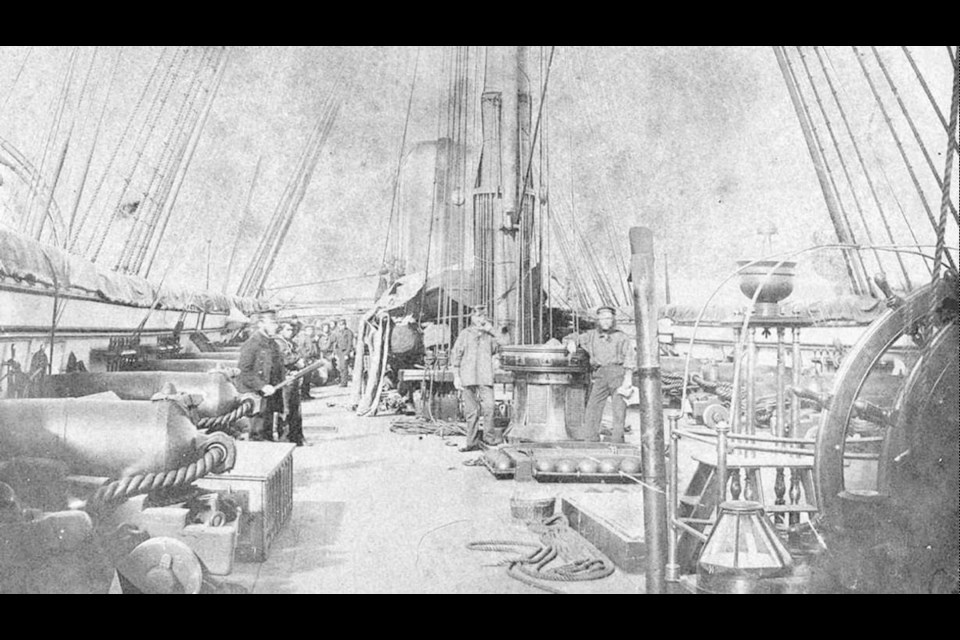

Douglas was in temporary command of the navy ships in the northwest waters. He ordered the 31-gun Royal Navy frigate Tribune to San Juan Island and instructed its captain to prevent any further landings by American soldiers.

“Please help me, for our troops are much outnumbered,” Pickett had written to Harney in early August.

With the letter came the official protest penned by James Douglas, claiming that the American occupation was illegal and that the San Juan Islands were British by right of claim that extended well before the American claim. Harney reacted in character. He sent Douglas a letter criticizing him for using a Royal Navy warship to carry out an arrest of an American citizen on behalf of the HBC — even though this had never happened. He then prepared to up the ante.

About 500 artillery, infantry and engineer officers and men were billeted to Fort Steilacoom, near the foot of Puget Sound, south of present-day Seattle. Harney ordered Lt.-Col. Silas Casey to lead these troops to San Juan.

On Aug. 17, 1859, four more artillery companies and a military band arrived at Griffin Bay and marched over the ridge to the American camp. The British offered no opposition to the landing of the troops. The American tally now stood at 15 officers, 424 soldiers and another 50 workmen. Standing off in Griffin Bay, the British now counted three ships, some 2,000 men — most of them sailors, not soldiers, plus a few hundred marines and Royal Engineers — and 167 ship’s guns. And word was that Harney himself was on the way with yet another 400 men.

Was war about to break out?

The Pig War: The Last Canada-U.S. Border Conflict, © Rosemary Neering, Heritage House Publishing, 20111