“Curiouser and curiouser!” remains one of Alice in Wonderland’s most famous statements, prompted when the immortal lass of Victorian literature has just eaten a cake that makes her tower nine feet tall.

And nobody could be curiouser about Alice than Victoria native David Day. The author of six bestsellers on the world of J.R.R. Tolkien, Day toiled mightily to unearth the bottomless “hidden meanings” that Alice originator Lewis Carroll buried throughout the classic work. “I think everybody knows it’s about something else, they just don’t know what it is,” he said in an interview from Toronto.

Day’s 41st book: Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland Decoded has arrived just in time for the 150th anniversary of the publication of the original Alice book in 1865, written by Oxford mathematician and clergyman Charles Lutwidge Dodgson.

Just how curious was Day? The one-time logger born in East Sooke spent 18 years down the rabbit hole of Alice research — obsessed, fascinated and undaunted in his quest to explain how and why her adventures were aimed both to enchant children with the goings-on, and amuse and perhaps enrage adults in the know about upper-class Victorian society.

Reading Alice as an adult, Day quickly realized he had never encountered writing quite like Carroll’s.

“It’s certainly the most complex work I’ve ever done,” said Day, acknowledging that even after 18 years, he finished it just before it went to press with Doubleday.

Day pored over more than 1,000 different editions of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland donated by a collector to the University of Toronto library. He read every one. Many times, he thought he couldn’t keep going. But ultimately, he just couldn’t let Lewis Carroll “get away” with all of the inside jokes and manipulations of English language and society.

“His language just got ahold of me. I wasn’t the only one who couldn’t let it go. James Joyce when he was writing Finnegan’s Wake was totally obsessed with Lewis Carroll. There are hundreds of verbal jokes about Alice in Finnegan’s Wake. Both he and Carroll were doing the same sorts of things with language and the manipulation of language.” And both were unparalleled at it.

His tome is dedicated to Roisin, his wife, and mentor Terry Jones, a member of Monty Python, others of whom collaborated on the film Jabberwocky, based on Carroll’s nonsense poem in Through the Looking-Glass.

Day points out that “three out of five Pythons endorsed the book.”

This is a book that discloses why the Cheshire Cat could disappear from grin to tail, delighting children and mathematicians alike (see sidebar). The Cat’s question: Are we mad while we’re dreaming or when we’re awake is “straight out of Plato’s Theaetetus” circa 369 BC.

When Carroll says that Alice’s great quality is her curiosity, it echoes what Socrates said: That a philosopher is a curious person. Her real-life inspiration was Alice Liddell (1852-1934) daughter of the dean at Oxford who was Dodgson’s superior.

Next to the works of William Shakespeare, Alice is the most quoted work by a single author, Day said.

Another 150th anniversary book has just come out, The Story of Alice: Lewis Carroll and the Secret History of Wonderland, written by Oxford English professor Robert Douglas-Fairhurst.

“It’s well-written but there really isn’t much new in it,” Day said. In his own? “Virtually everything is new. There have been people who hinted about the real identities, but nobody has taken it to the extent that I have. And the identification of the mythological level and the mathematical level,” he said. Douglas-Fairhurst declined to comment to the Times Colonist.

Day took his manuscript to Francine Abeles, the world’s academic expert on Lewis Carroll’s mathematics, for a read-through and said she approved of Day’s take over that of a woman who earned a PhD on the subject of the math in Alice.

No one before has looked at Fibonacci’s rabbits rule and how it applied in Alice, he said (see sidebar). He says that Alice’s fall down the rabbit hole echoes a mathematical “thought experiment” employing an infinite series of numbers called Fibonacci numbers, based on the reproductive rate of a pair of imaginary rabbits.

“I think a lot of people first experience it through the Disney film, but it seems like every second book on mathematics and physics has a quotation from Lewis Carroll. Politicians, too. Alice has something for all of them,” Day said.

Far from just a little girl in a pinafore, Alice stands in for Persephone, Greek goddess of spring, in her descent to the underworld, one of the oldest recorded myths.

Many people first experience Alice through the saturated colours of Walt Disney’s 1951 animated feature.

“It’s an entertaining version of it — certainly closer than the Johnny Depp version, which combines the two [Alice books] and totally messes them up,” he said. Less well-known is that Disney built his cinematic empire on Alice, having produced 26 short films based on the novel in the 1920s.

Day didn’t have any particular yearning to write about Alice and Dodgson/Carroll. The project began when he was living in England in 1996 and another publisher suggested he write a book marking the 100th anniversary of Carroll’s death in 1998. Day remembers thinking: “Well, I’ve done all this material on Tolkien — it can’t be that difficult. Look what a small book [Alice] is.”

Famous last words.

“I just started reading and realized that I just got deeper and deeper.” There would be no book for 1998. He devoured everything he could find in the British Museum Library, the London Library, the Oxford University libraries.

The home Alice grew up in, the Oxford deanery, is still standing. “She grew up as a little princess, that’s for sure.” By way of home decor, a painting by John Turner was in the parlour.

Carroll fell for Alice when she was 10 or 11, the middle of three daughters of his academic superior at Christ Church, Oxford, Henry Liddell and his wife Lorina.

The little boat ride on which Alice asked Dodgson to tell her a story lives in literary history, and was followed by 10 or 11 more nature-based outings. Then the Liddells drew the line, devastating the shy bachelor scholar.

Carroll took his revenge by making the King and Queen of Hearts — standing in for real Liddell names — “homicidal maniacs,” Day said.

Forbidden to spend real time with his “dream-child,” he wrote Wonderland as his eternal gift: a classical education conveyed to her by subliminal symbols and language that conveyed “a higher truth straight to the soul, bypassing the intellect,” Day explains.

Even though the era allowed girls to get engaged at 14, bachelors taking pubescent girls on outings was “just inappropriate,” Day said. Carroll also took a couple of thousand photos of children, including some in the nude. The pages in Carroll’s diary that refer to the visit that cut off contact were removed, likely by the author’s nieces, Day said. Not that anything physical occurred, in his opinion.

“I think he’d probably have to kill himself if he had to have sex with anybody,” Day said. “He was someone who was celibate all of his life. To teach at Oxford at that time, you had to be celibate. If you married, you would lose your job.”

After that, Carroll had only occasional contact with Alice.

“She got married at Westminster Abbey and she didn’t invite Lewis Carroll,” he said. Eventually, she sold her Alice papers for “a small fortune” — more than 15,000 pounds sterling in 1926 and received an honorary doctorate from Columbia University in 1932, the centenary of Carroll’s birth.

“She was running out of money; the aristocracy was having a hard time (and) she was a bit tired of being Alice,” he said.

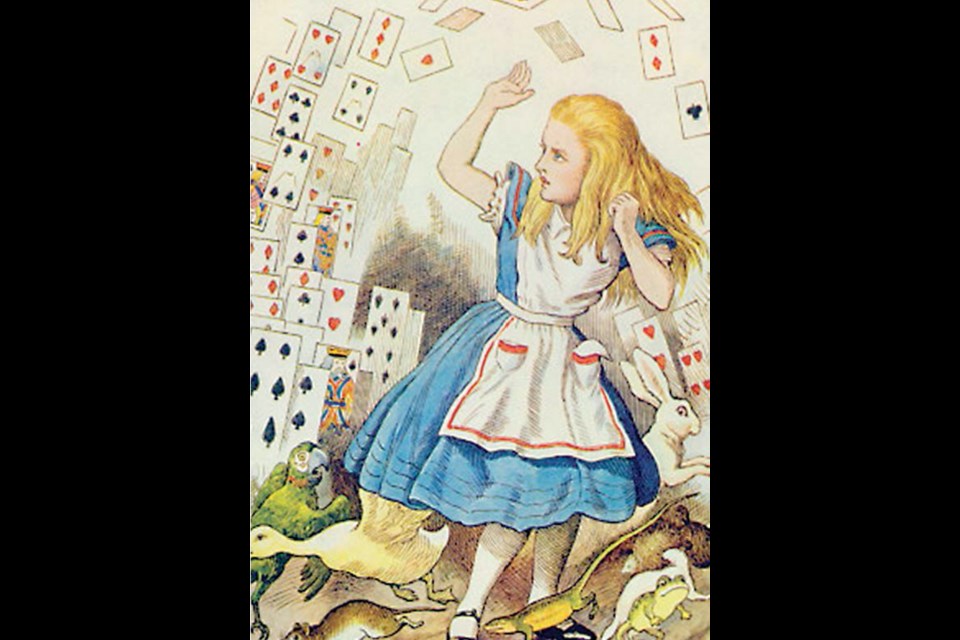

Of all the illustrations that have depicted Alice over the centuries, he still prefers the originals by John Tenniel.

“I don’t think you can really improve on them. I think they’re the ones that hold people best.”

The copyright expired on the book seven years after publication, but the copyright on the drawings lasted for much longer.

“Consequently, every major illustrator from 1907 onwards has been illustrating different versions of it.”

Will there be a sequel to this Alice? Day is not ruling it out.

“I think it would only take a couple of years. I might, I might, I might.”

10 things you never realized about Alice

In Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland Decoded, David Day writes of Alice author Lewis Carroll’s “multi-layer world inhabited by characters with multiple identities.”

Indeed.

Here is an abbreviation of Day’s list of 10 Things You Never Knew About Wonderland:

1. THE OLDEST STORY IN THE WORLD

Originally called Alice’s Adventures Under Ground, Carroll’s tale evokes the oldest of all recorded myths, that of the Mesopotamian goddess Inanna’s descent into the underworld, retold by the Greeks as Persephone’s return as the goddess of spring.

2. WHAT’S IN A NAME?

The Oxford mathematician Charles Lutwidge Dodgson created the pseudonym Lewis Carroll by translating Charles Lutwidge into Latin — Carolus Ludovicus — then reversing their order and re-translating them to English.

3. THE “REAL ALICE”

Alice Liddell was the daughter of Henry George Liddell, dean of Lewis Carroll’s college of Christ Church. Alice’s father and mother became the King and Queen of Hearts. The Caterpillar was Thomas de Quincey, author of Confessions of an English Opium-Eater. Bill the Lizard was future prime minister Benjamin Disraeli, while the Dodo was the stammering Do-Do-Dodgson himself.

4. DOWN FIBONACCI’S RABBIT HOLE

Alice’s fall down the rabbit hole echoes a mathematical “thought experiment” employing an infinite series of numbers called Fibonacci numbers, based on the reproductive rate of a pair of imaginary rabbits.

5. THE TELEPATHIC CATERPILLAR

Alice discovers the Caterpillar is capable of reading her thoughts, a reference to Carroll’s lifelong interest in telepathy, calling it “a natural force, allied to electricity and nerve-force, by which brain can act on brain.”

6. WHO LIVES IN WONDERLAND?

Largely imaginary beings that exist only as figures of speech or as characters from rhymes, fairy tales or myths, such as the Mad Hatter or March Hare. In Wonderland, real creatures such as hedgehogs are treated as objects, while playing cards behave as if alive.

7. THE CHESHIRE CAT’S GRIN

“To grin like a Cheshire Cat” was a saying dating to the 1700s, but Carroll morphed it into a play on words and geometry. When Alice describes the apparition of the departed Cheshire as “a grin without a cat,” she is mouthing a mathematical solution to an ancient riddle: “What kind of cat can grin?” A catenary — the curve made by a chain suspended between two points.

8. FINDING THE RIGHT DICTIONARY

In Through the Looking-Glass, the Red Queen explains: “You may call it ‘nonsense’ if you like, but I’ve heard nonsense, compared with which that would be as sensible as a dictionary!” Many Wonderland inhabitants use everyday words accessible only to a philosopher, hence the necessity of a decoding dictionary.

9. RIDDLE OF HATTER’S HAT

The numbers and words on the Mad Hatter’s hat are clues to Fermat’s Theorem, linked to the exponential growth of “Mile High” Alice.

10. A MEMORY PALACE

Wonderland is a time capsule of the Victorian Age. Clergyman Carroll used subliminal symbols and language “to convey a higher truth straight to the soul, bypassing the intellect” with Alice’s Adventures his gift of a classical education delivered subliminally to his “dream-child.”