Recently, Emily Urquhart, a Victoria writer and folklorist, took her four-year-old daughter Sadie to a birthday party.

As a treat, all the little girls were given “princess” hairdos. One adult made a comment about Sadie.

“She said, ‘Look at that child’s hair. Is it really that white, do you think?’ I was thinking, ‘Sure it is,’” Urquhart said.

Sadie is an energetic, lively girl who loves her little brother and riding her scooter. She was diagnosed with albinism — hence the white hair. Because her vision is impaired, Sadie wears glasses (the frames are yellow, her favourite colour).

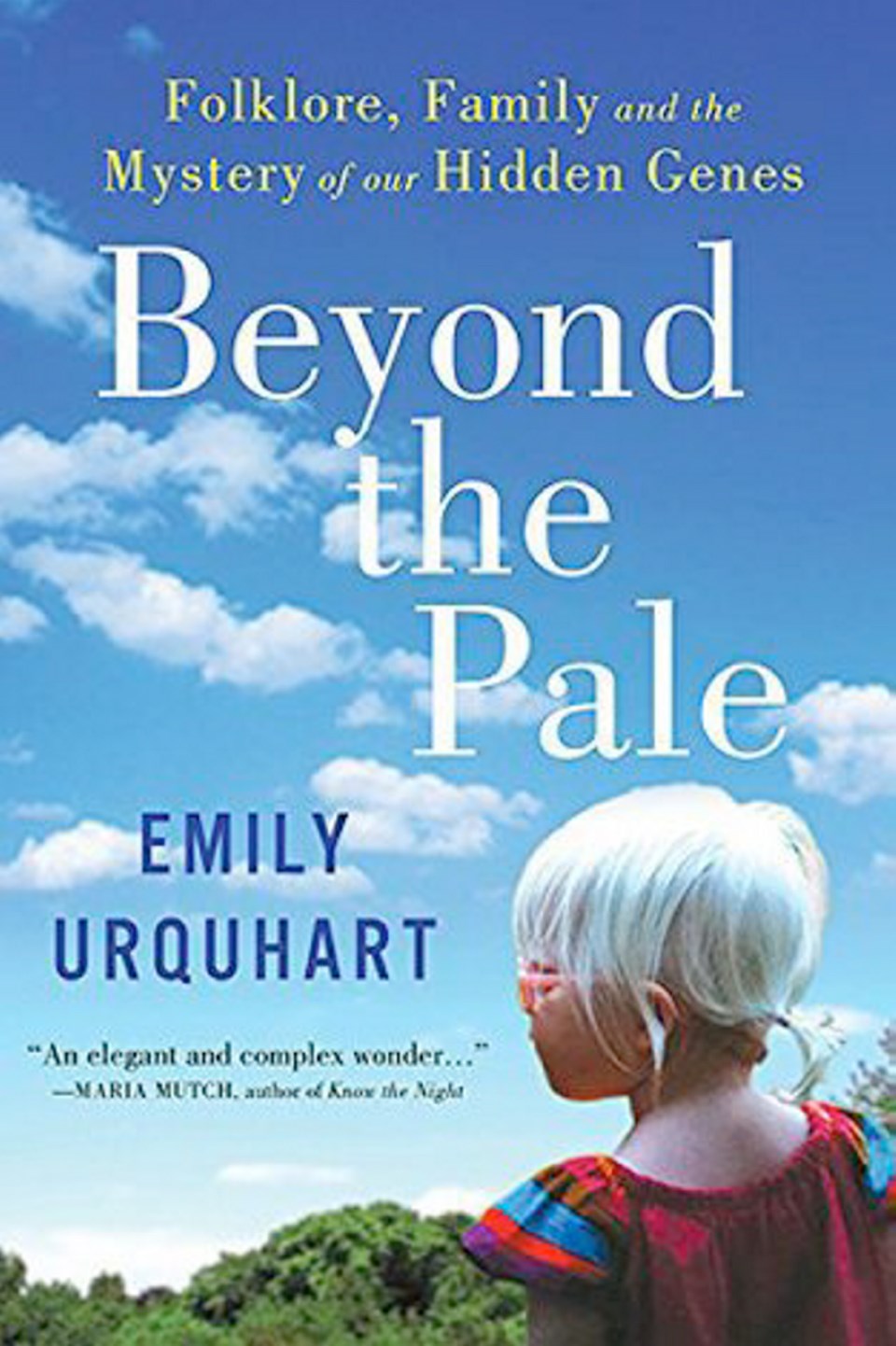

The daughter of best-selling novelist Jane Urquhart, Emily has written a new memoir about being Sadie’s mother. Beyond the Pale — Folklore, Family and the Mystery of Our Hidden Genes is about Urquhart’s experience of exploring and understanding life as the parent of a child with albinism.

Albinism is caused by a recessive gene carried by both parents. There are different forms; however, it is typified by a lack of pigment in skin, hair and eyes. In the U.S., about one in 20,000 people has albinism, according to the National Organization for Albinism and Hypopigmentation.

I spoke with Urquhart at her Victoria home. Sadie was at daycare; the girl’s colourful artwork was proudly displayed on the family’s fridge. Urquhart said her daughter’s albinism was officially diagnosed when she was three months old.

Before that, her husband Andrew had his suspicions, which he diplomatically kept them to himself. Urquhart remembers shortly after the birth, a hospital janitor had asked if the white-haired newborn was “an albino.”

“I just thought she was a nut case,” Urquhart said with a wry laugh. “But I should have listened to her.”

Two weeks after Sadie was born, her father-in-law, a physician, came to visit. He thought the baby might have albinism. And this time she listened.

“When he suggested it, I didn’t want to hear it. You reject the diagnosis. The same day he suggested it, I called my mom. By the time, I knew. And I knew it wasn’t going away,” Urquhart said.

As well as exploring her own experiences, Beyond the Pale looks at how albinism is viewed in cultural history (Urquhart’s PhD in folklore equips her for such research). She writes about historical reports of albino colonies in Massachusetts.

The book also led her on a journey to Tanzania, which has an unusually high rate of albinism. The East African country is notorious for its treatment of the afflicted. Superstitious Tanzanians believe the body parts of people with albinism have magical powers. Because there’s a lucrative black-market trade, this leads to dismemberments and murders.

Urquhart says it was difficult talking to young people with albinism in Tanzania, some of whom were survivors of horrific violence. On the other hand, it provided context for her own daughter’s considerably safer situation.

“It was definitely harrowing,” she said. “It was awful, as a new mother .... But seeing that firsthand put it into perspective.”

In 2012, Urquhart met up in Vancouver with a teenage Tanzanian boy with albinism. Adam Tangawizi’s father and stepmother had sold him to a machete-wielding stranger who tried to dismember him. Although his fingers were chopped off, the boy survived.

In some ways, the meeting was curiously comforting. Urquhart showed Adam pictures of Sadie. The teen giggled at times and drew pictures.

“He was just this goofy kid. He had suffered. But he was happy enough, I guess,” she recalled.

Of course, in North America people with albinism aren’t mistreated in such a manner. But Urquhart notes they are sometimes viewed as being other than “normal.”

In Beyond the Pale, she writes: “I bristle when people refer to Sadie as an albino but not because I am offended. The term suggests she belongs to a different tribe than my own.”

There are many inaccurate stereotypes about people with albinism: They have pink eyes, they are blind, they are mentally impaired or they possess supernatural powers.

“My understanding is when people don’t understand something or fear something, they create these places of ‘otherness’ where those people might exist. In North America it’s not as tragic or heinous as Tanzania, but it’s still separating people and seeing them as different,” Urquhart said.

Sadie is legally blind, yet with glasses she manages to function like any other little girl. Nonetheless, Urquhart says it’s hard not to be overprotective. Sadie enjoys riding her scooter to pre-school, zipping ahead of her mother.

“I just hope she can stop on the corner and hear cars and see people,” Urquhart said. “I’m sure all parents feel this way. But I have this extra fear.”

In January, Urquhart and her husband had their second child, a boy named Rory. Before his birth, she underwent tests for albinism, which Rory turned out not to have.

Urquhart says she would not have hesitated to have another child with albinism.

“You just have to come to that conclusion, because there was a very high chance the next child you had would have albinism. There was a one in four chance.

“But I guess finally, in the end, I was OK. It was going to be OK.”

The Victoria launch for Beyond the Pale with Emily Urquhart will be held at the Bard & Banker on Wednesday, May 13, from 6 p.m. to 8 p.m.