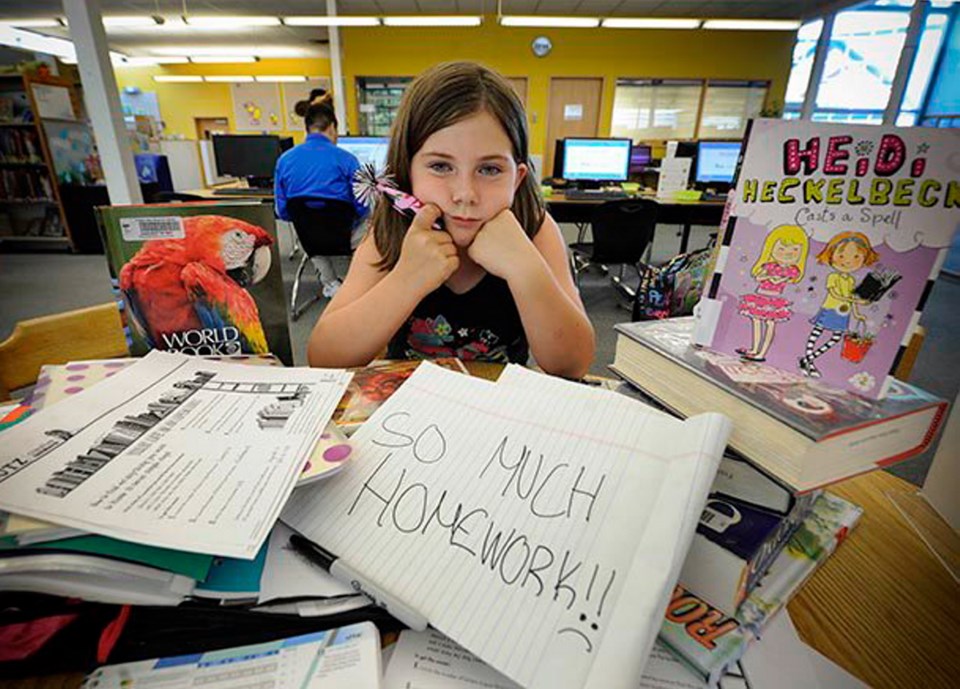

Bev Shaughnessy says she and her daughter are being eaten alive by the homework monster.

Arieanna, a Grade 4 student in Delta, gets at least 10 hours of homework a week, according to Shaughnessy.

The nine-year-old girl would like to play baseball, ride horses and cheerlead. But there s no time, Shaughnessy says. One night a week of Brownies is all they can manage.

“The poor kid is run ragged. It’s overwhelming and very stressful. She can’t sleep and I’m so wired I can’t sleep,” Shaughnessy says. “I’m at my wits end.”

As the school year heads to a close, many parents are questioning whether their children have received too much or too little homework.

An informal online probe by The Province of 341 B.C. parents of children in Grades 1 through 12 shows widespread unease with homework volumes.

Thirty-eight per cent of parents — more than one in three — say their kids are getting too much homework. Twenty-six per cent say they re not getting enough, while 36 per cent say it s just right.

Twenty-three per cent of parents report that their children get five to 10 hours of homework a week, while 14 per cent say it’s more than 10 hours.

Homework, long a battleground between teachers, parents and students, is coming under more scrutiny than ever as the divide grows between resisters and proponents.

Teachers are assigning it but many students don’t bother to do it.

Parents’ negative attitude to homework generally intensifies as the amount of homework grows, according to one study.

Other research has found that parents resistance to homework can affect a child’s attitude toward school as a whole.

A few elementary schools across the country have banned homework. One in Barrie, Ont., found marks went up following the ban.

REINFORCING MISTAKES

Parents who feel their children are being assigned too much homework say it’s cutting into other activities.

“What happens when homework takes away all the negotiable time from children so that play and recreation, hobbies, friendship development and creative activities are usurped?” the Canadian Education Association asks in a recent paper.

“This can’t be good. Children need time to relax and renew.”

Homework can aggravate mental health challenges by adding stress to students’ lives. A 2008 survey of parents by University of Toronto researchers is peppered with caregivers’ comments about burnout and low self-esteem. And the rigours of children’s homework can even put stress on their parents marriage, the survey found.

Homework can also trigger tension between different cultural groups in which parents have conflicting expectations of how much is needed, experts say.

Even its proponents concede that poorly designed or inappropriate homework may hurt student achievement.

Research over the past 10 to 15 years shows homework to be an exercise that would have some merit to it but not a whole lot, says Ron Canuel, president-CEO of the Toronto-based CEA, a non-profit group whose members include school boards, teachers and other educators.

UBC education professor Sandra Mathison says lots of homework at the elementary level does little to help make kids better students.

“At the elementary level there is very little evidence to suggest that homework contributes very much to academic achievement,” says Sandra Mathison, a University of B.C. education professor.

“At the secondary school level, there is more evidence to suggest that homework has a potentially positive impact.”

Homework’s defenders cite what Mathison calls its morals-building capacity its ability to nurture a strong work ethic, self-discipline and sustained concentration.

“There’s nothing wrong with that but, frankly, I don’t think many of the forms of homework accomplish this,” she says.

Homework that simply extends the school day by asking students to repeat what they re doing in class is not productive, Mathison says.

“Homework that gives students ‘practice’ like math worksheets, spelling words, vocabulary has a common-sense appeal, but in many cases repetition of activities is no guarantee of understanding,” she says. “If students haven t mastered the knowledge or skill they may be reinforcing mistakes and misconceptions, and homework may lead to frustration and be de-motivating for students.”

Kathy Sanford, a University of Victoria education professor, says that without the support of thoughtful learning in class, students may not even know how to start homework.

“This is frustrating for the learner and parent, and meaningless,” Sanford says.

10-MINUTE RULE PROPOSAL

Phil Winne, an education professor at Simon Fraser University, says studies show “pretty strongly that homework is a good thing as long as you re sent home well prepared to do the work.”

Winne points to a 2006 study that found an average student given appropriate homework scored 23 percentile points higher on tests than an average student who was not assigned homework.

“There are a lot of conflicting messages and the poor parents are trying to figure out what’s best,” says Sanford. “Parents are frustrated with the amount of time expected to be spent on homework and want their children to have other quality time.

“There are a lot of reasons why homework is really an impediment for families.”

Experts are divided on how much homework is too much or too little or whether it should be assigned at all.

They agree, however, that quality of what is assigned is more important than quantity.

“Not all homework is created equal,” says Winne. “It’s not the time per se that matters but the characteristics of the work and the readiness of students to do it.”

Poorly structured homework for which students have been inadequately prepared in class may actually do harm.

“The positive effects of homework relate to the amount of homework that the student completes rather than the amount of time spent on homework or the amount of homework assigned,” say American researchers Robert Marzano and Debra Pickering.

Some researchers have proposed a 10-minute rule for homework. This means that all daily homework assignments combined should take 10 minutes multiplied by the students grade level.

The 10-minute time frame can be extended to 15 when required reading is included.

Mathison says homework lasting more than 30 minutes daily for elementary students and one to two hours across all subjects for secondary students is unproductive.

“If kids are overburdened with extra work, we run the risk of disillusioning them from schooling overall,” Sanford says.

PARENTAL SUPPORT

Parents play a key role by supporting learning outside of school and monitoring their children s progress regularly, says the Canadian Education Association.

“It is important to be positive,” the association advises parents. “If homework leads to bad feelings between parents and children, it can have negative effects on both school and home relationships.”

A 2008 study by University of Toronto researchers found that 75 per cent of parents believe their children now have “somewhat” to “much more” homework than they did as children.

But nobody is putting homework on an endangered-species list. According to OECD research, the amount of time 15-year-olds in Canada spend on homework has shown little change between 2003 and 2012.

“Personally, I think that a little bit of homework is a good thing. It suggests to students that there is learning to be done outside the walls of the classroom,” Winne says. “There is an opportunity to take more responsibility for your learning. It creates space for investigating things of great personal interest.”

The world doesn t need people who are good at memorizing things, Sanford says. It needs people who can ask good questions, analyze and work collaboratively.

“I don’t think (homework) is changing fast enough,” Sanford says.

“We have lots of work to do.”

If there is one thing about out-of-classroom learning on which educators agree, it s the need to read.

As a result, homework is expanding to include activities that engage students in reading large amounts of text.

Relevant activities range from online research to cooking to fiction to taking photos, making videos and building models.

Chilliwack parent Scott Verwold believes homework can play an important role in children s lives by preparing them for eventual life outside the classroom and by building their work ethic.

But his daughter Davina, a Grade 4 student, is assigned no homework, says Verwold.

In previous years, Davina got more homework and did extra work voluntarily.

Now that she gets none, the idea of doing extra seems onerous to her, Verwold says.

Verwold is disappointed by her teacher s no-homework policy and worries the lack of homework may affect her future.

“We’re in a very competitive day and age and it’s getting to be more so,” Verwold says.

“It seems like schools are not preparing our kids for the competitive worlds that they will be entering in a few years.”

TEACHERS TAKES ON THE OFTEN THORNY ISSUE

Tanis Maxfield has been in the thick of the homework debate from two sides.

As a teacher and a parent, she has witnessed the range of opinion on homework and learned when to assert and when to accommodate.

“You get parents who don t believe in homework and those at the other end of the spectrum who want a daily homework regimen,” the Grade 6 French immersion teacher says.

“Some believe in homework but do not feel it s important to be on top of their children and make sure they are doing it.”

Still others have told Maxfield that it s more important for their children to take part in sports or music. Those parents don t want homework to detract from these pursuits.

Her suggestion to parents across the spectrum is to encourage their children to read.

For French immersion students, this ideally means 10 to 20 minutes reading in English and French. Maxfield says reading sources can include magazines, websites and graphic novels.

Maxfield, who has two teenage daughters, has also been subject to teachers varying approaches to homework. Some have assigned large volumes of nightly homework, others have assigned none.

She says her children have benefited from having to adjust to a variety of homework philosophies.

“You want your children to be able to accommodate a wide range of people, expectations and workloads,” Maxfield says.

They must adjust to a wide range of differences if they re going to be resilient and follow a successful path through life.

Jonathan Dyck, a high-school math and English teacher in Langley, says homework can be overdone and overused.

Dyck does not formally assign homework in math and leaves it open to students if they wish to practise more at home.

Dyck especially encourages students in the senior grades to take charge of whether they should do work outside of the class.

“Most really appreciate that approach,” he says. “It prepares them for the transition to post-secondary, where they have to be more self-directed.”

A B.C. Ministry of Education spokesperson said the ministry does not have any regulations, laws or provincial policies on homework.

B.C. Teachers’ Federation president Jim Iker says the teachers union has no formal policy on homework. Iker says he personally believes teachers should have the independence to tailor a homework strategy to best serve the diverse needs of students.

Economically disadvantaged children will find homework more of a struggle than others, he says.

“When you have kids come to school without any breakfast and sometimes without lunch, how can you expect them to do homework?”

Research shows that advantaged 15-year-old students in OECD countries spend an average of 5.7 hours a week on homework, while disadvantaged students average 4.1 hours a week.

“Advantaged students are more likely than their disadvantaged peers to have a quiet place to study at home and parents who convey positive messages about schooling,” one researcher says.

HOMEWORK HOURS AROUND THE WORLD

In 2012, 15-year-old students around the globe spent an average of 5.9 hours a week doing homework, one hour a week less than in 2003, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development says.

The decline in homework may reflect the growing importance of the Internet in adolescents lives and changes in teachers ideas about whether to assign homework, and how much is adequate or too much, the OECD says.

“Evidence … suggests that after around four hours of homework per week, the additional time invested in homework has a negligible impact on performance,” the OECD says.

The following is a list of the average hours of homework per week assigned to students in select countries, chosen from a table published by the OECD in 2012:

Shanghai-China: 13.8

Russia: 9.7

Singapore: 9.4

Italy: 8.7

U.S.: 6.1

Australia: 6

Hong Kong: 6

Canada: 5.5

Mexico: 5.2

U.K.: 4.9

Germany: 4.7

New Zealand: 4.2

Japan: 3.8

South Korea: 2.9

Finland: 2.8