Every house has a story to tell.

It may be about a challenging building site, a shocking overrun during renovations or some interesting architectural elements.

But this house is more self-effacing. It doesn’t scream “look at me” or boast about showy countertops, engineered floors and glazed walls. Instead, it reveals the story of two globetrotting owners and is a storehouse of memories of their far-flung travels and careers.

Goetz Schuerholz built the house in 1977, carefully leaving most of the surrounding two-hectare forest property untouched.

He envisioned a home that would disappear into the landscape.

“I adapted it to the geomorphology,” said Goetz, who was born in Germany, has a doctorate in wildlife ecology and studied at both the University of Freiburg and UBC.

Stationed in Rome, he first worked for the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations and was responsible for wildlife conservation projects in Africa and Asia. He then transferred to Santiago, Chile, where he led wildlife and conservation activities in Latin and Central America,

His wife, Beate Weber Schuerholz, has had an equally interesting career. As mayor of Heidelberg, Germany, from 1990 to 2006, she guided that city to reduce its CO2 emissions by a staggering 30 per cent during her term of office and is credited with helping that nation move toward energy sustainability.

She has been named Honourary Freeman of the city of London, Chevalier de l’Ordre National de la Légion d’Honneur (France’s highest decoration) and Woman of the Year in Germany.

She also just won the Gothenburg award for sustainable development in the field of energy efficiency — previously won by Norwegian prime minister Gro Harlem Brundtland and former Secretary-General of the UN Kofi Annan.

The two live in what they call “splendid isolation” in a 2,800-square foot, metal-roofed home overlooking Cowichan Estuary.

Rather than being on the water, their elevated property offers a more acute angle on “a very dynamic estuary that teems with wildlife,” said Goetz.

Designed in the California style, with naturally weathered exterior wood and cedar ceilings, the house features three wings radiating from a central hub.

Goetz also built a smoke-house, sauna, woodshed, adobe oven and deck that juts out over the sloping property. “I wanted to live in the canopy of the forest. Here we are in the treetops where there is totally different wildlife and we are well hidden.”

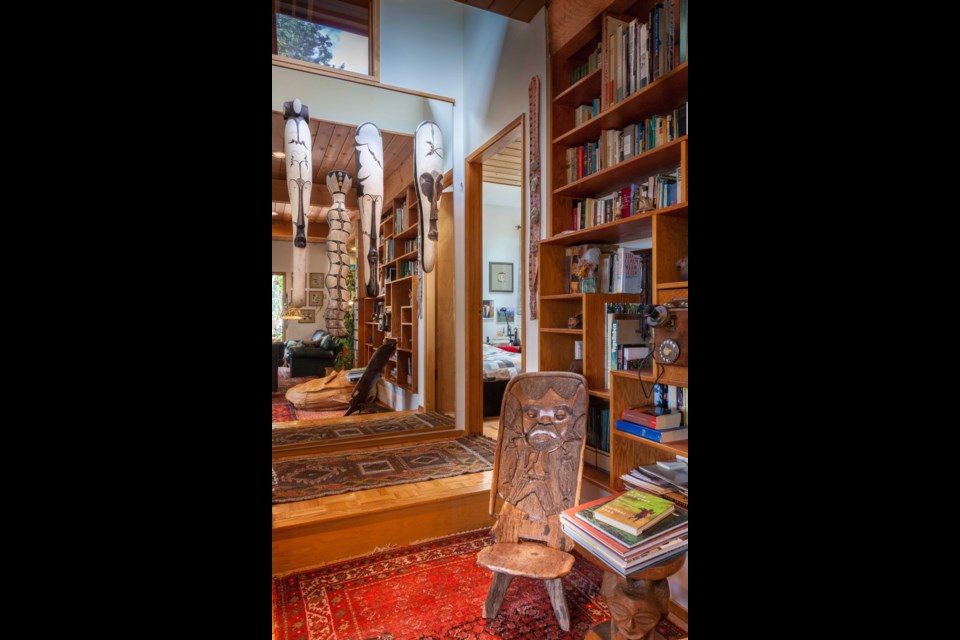

Their home is casual, comfortable and crammed with everything from the skins of a giant anteater, python and zebra to spears given to Goetz by natives of the south Sudan and shields from Afghanistan. The coffee table is carved from a single piece of wood and was once a bushman’s bed.

“Wherever I went, I would collect pieces,” said Goetz.

The couple’s museum-like home includes a shaman stick from South America, exotic masks, a whale skull, the skin of a caiman (alligator) and one of Beate’s favourites — a raft of hippos sculpted in African wood and stone.

One of his most treasured items is a toucan feather headband given to Goetz when he was made honourary chief of the Achuar Indian tribe, a remote culture in the upper Amazon.

Because the conservation ecologist’s passion is art, he is also adding to the world’s culture himself by creating paintings and sculptures in a new, high-ceilinged studio he recently built.

The two have been together almost seven years — “Not long enough,” said Beate with a chuckle — and met at an environmental conference when she headed a German commission on the environment. “We started talking and never stopped.”

Goetz had loved Canada since studying at UBC — “it was a childhood dream to come back … Jack London and all that.” After leaving the UN, he moved to B.C. and formed an environmental consultancy business, working on biodiversity conservation and sustainable management with agencies worldwide.

He bought land at Cowichan and a guiding area in the Cariboo Chilcotin, which he later helped convert into a class A provincial park called Tsylos — the highest conservation status of any protected area in B.C.

Beate always loved Canada too, after visiting as a European MP and chairwoman of the International Council for Local Environmental Initiatives’ commission on the environment. The international group of local government organizations is committed to sustainable development and has a membership of more than 1,200 cities, towns and associations in 84 countries.

“At that time, Canada was very, very environmentally concerned and a leader in environmental issues,” she recalled. “Now the Harper government is driving us backwards, destroying the environmental and military reputation of this country.”

While Goetz and Beate are now retired, they are working to restore the ecological integrity of Cowichan Estuary. (See story, Page E9)

“Neither of us care about countertops; we care about other things,” said Beate, who speaks five languages and doesn’t watch television. “We are interested in people, in ecology and in equality.

“Never in history have we seen such displacement of people, such terrible urban sprawl, such drying up of rivers and desertification.”

Fundraiser aims to help restore estuary

What: Cowichan Estuary Restoration & Conservation Association dinner and auction

Where: Arbutus Ridge Golf Club

When: 6 p.m. Friday, Oct. 9

Tickets: $150. For information call Beate or Goetz Schuerholz at 250-748-4878, or see cowichanestuary.com

Cowichan estuary is one of the most important ecosystems on earth and one of its key roles is carbon sequestration — removal of carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, says Goetz Schuerholz, founding member of Cowichan Estuary Restoration and Conservation Association.

The group is holding a fundraising dinner Oct. 9 to support reclamation projects in the estuary, as well as construction of an open classroom and nature trails.

The evening will feature a buffet dinner with matching wines and an art auction. Former Irish Rover Will Millar will provide entertainment, along with Grammy-nominated pianist Michael Creber.

Schuerholz says about half the estuary has been negatively affected by forestry-related industries, but it still has “high restoration potential.”

“The Crofton paper mill takes up to 36 million gallons a day out of the lower Cowichan River, and discharges treated water into the sea. It would be a great help if some of this water could be recycled. If, for instance, only five or 10 million gallons could be used from the river.”

Fresh water is essential in the estuary, as it mixes with salt water and enables mud flats, marshes and tidal areas to thrive.

“We want to make it a working estuary again, and by that I don’t mean industry,” he says. “An estuary should be a cradle of life in the ecological sense.”

The estuary is the fourth largest and one of the most precious on B.C.’s coast, Schuerholz says, because of its size and the fact it is enclosed in a bay and two rivers flow into it — the Cowichan and Koksilah. One of his biggest concerns is log booms that “ground out” at low tide, destroying the “absolutely crucial eel grass.”

This prevents a unicellular algae forming on the surface and, through photosynthesis, taking carbon dioxide out of the air and releasing oxygen.

Last year, the association used $320,000 in government funding to breach an artificial dyke built in the estuary in the early 1900s.

The dam previously had a rail line running along it to a now-decommissioned dock.

The hole allows water to circulate freely on both sides of the estuary again, which helps salmon, too, Schuerholz says.

— Grania Litwin