TORONTO — Dr. Eugene Chang lost 50 pounds he couldn’t afford to shed, but found a calling when he had cancer treatment at age 25. The challenges Chang faced battling his way back to health after his bout with his disease inspired the rehabilitation medicine specialist to rethink his career.

He decided to pursue a subspecialty for which there is a growing need, becoming Canada’s first trained cancer physiatrist. A physiatrist is a doctor who specializes in rehabilitative medicine.

According to Dr. Gaetan Tardif, medical program director for rehabilitation and physiatrist-in-chief at Toronto Rehab, where Chang now works, society does not do enough to help people with cancer minimize the physical toll the disease and its treatments take on patients.

While the notion of rehabilitation after a heart attack or for people who have had strokes or spinal-cord injuries is well established and even expected these days, the need to address the impact of cancer has not kept pace.

“If you have a stroke, nobody these days is thinking: ‘Yeah, we’ll send a physiotherapist for a few minutes a day and things should be OK,’ ” Tardif said.

“But in cancer, we haven’t developed that thinking that ... we need a team of people. We’re not quite going far enough in getting people to function optimally in the community.”

Nick Marks knows from personal experience that it can be a real struggle.

Marks, 70, is a semi-retired benefits consultant living in Toronto. In July 2013, he learned he had multiple myeloma, a type of cancer that attacks white blood cells called plasma cells.

The disease, which can be managed but not cured, impedes a person’s ability to mount an immune response to invading pathogens such as bacteria and viruses.

In the process of his treatment, Marks contracted C. difficile diarrhea, landing in hospital for two months. A slender man, and one who professes to hate exercise, Marks could not walk by the time his C. difficile was cured.

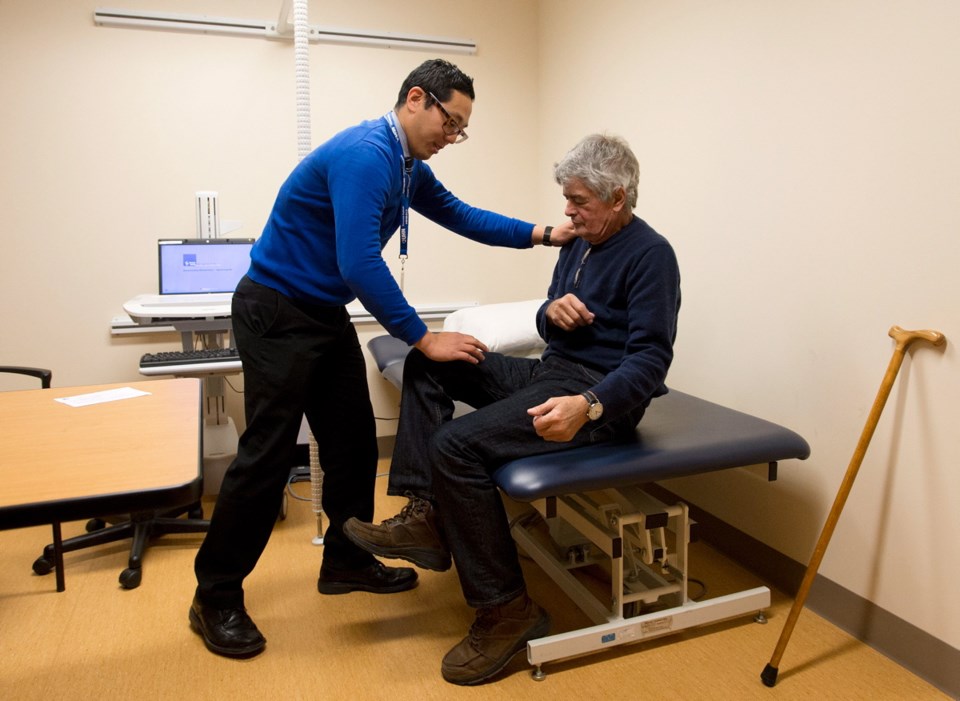

He has been working with Chang to regain his mobility.

“You really have to relearn to walk and I’m still doing that,” he said.

The two work on strengthening Marks’s legs. Motivated to get rid of the cane he still uses, Marks is walking, climbing stairs and doing exercises that target his thighs.

Chang, too, learned of the importance of this rehabilitation medicine first-hand.

In the autumn term of 2005, he started a residency in physiatry at the University of British Columbia. “I thought I was going to do sports [rehab] or something like that. I had no clue of my journey at the beginning of my residency,” he said.

An active guy who cycled to work and played hockey in his free time, Chang suddenly found normal exertion was making him breathless and fatigued.

A blood test, followed by a bone-marrow test, produced an unexpected result. He had myelodysplastic syndrome, a cancer affecting the bone marrow.

Chang’s medical career took a two-year hiatus as he underwent chemotherapy and then a bone marrow transplant. The transplant was a success, and, nine years later, he remains cancer free.

But the treatments left him weak and in need of rehab medicine himself. Chang found he had to push to get the care he knew he needed.

“That was a real eye-opener,” he said. “This was not a good thing and maybe this was a problem in cancer generally.”

When Chang went to resume his rehabilitation medicine training in the fall of 2007, the experiences of his time as a cancer patient had changed his thinking about what his focus should be. Sports rehab was out, cancer rehab was in.

Some of the effects of cancer care are specific to the type of the disease. For example, a stiff shoulder can sometimes follow a mastectomy for breast cancer patients.

Others are general, such as fatigue, muscle wasting and sometimes neuropathy, the loss of nerve cells in feet and hands that can affect a person’s gait.

Too often with cancer, people see the disease as a reason to give up on exercise and physical conditioning, Tardif said. Everyone pays the price for it, he added.

“Are we quitting a little too early on the full community reintegration? Are we focusing too much on just fixing the medical problem? But then what? And the better we get in medicine at fixing problems, the more important the ‘then what?’ is,” he said.

“Frankly, I want somebody to save my life. But if I’m going to be miserable for the next 10 years at home, I’m going to have second thoughts about how good that deal was.”