If you want to learn to colour outside the lines, you must embrace the Trickster. So says Victoria author and artist Nick Bantock, the creator of Griffin and Sabine.

Put another way, if you want to be genuinely creative — that is, tap into the best stuff from your deeper self — you’ve got to go with your instincts rather than logic. It’s not easy, because it seems counterintuitive.

Bantock has just published The Trickster’s Hat: A Mischievous Apprenticeship in Creativity. In the 194-page book, published by Perigee Books, he offers advice and 49 exercises to spark and encourage creativity.

When it comes to being creative, Bantock is a good guy to take advice from. For starters, he’s taught workshops on creativity for a dozen years.

As well, Bantock is the author of the massively successful Griffin and Sabine trilogy. The popular books, which combine text with imaginative illustrations, spent more than 100 weeks on the New York Times bestseller list. More than five million copies sold worldwide.

Bantock is a native Briton who lived on Saltspring Island before moving to Victoria nine months ago. He lives in a shingle-clad, uncluttered home near Cook Street Village.

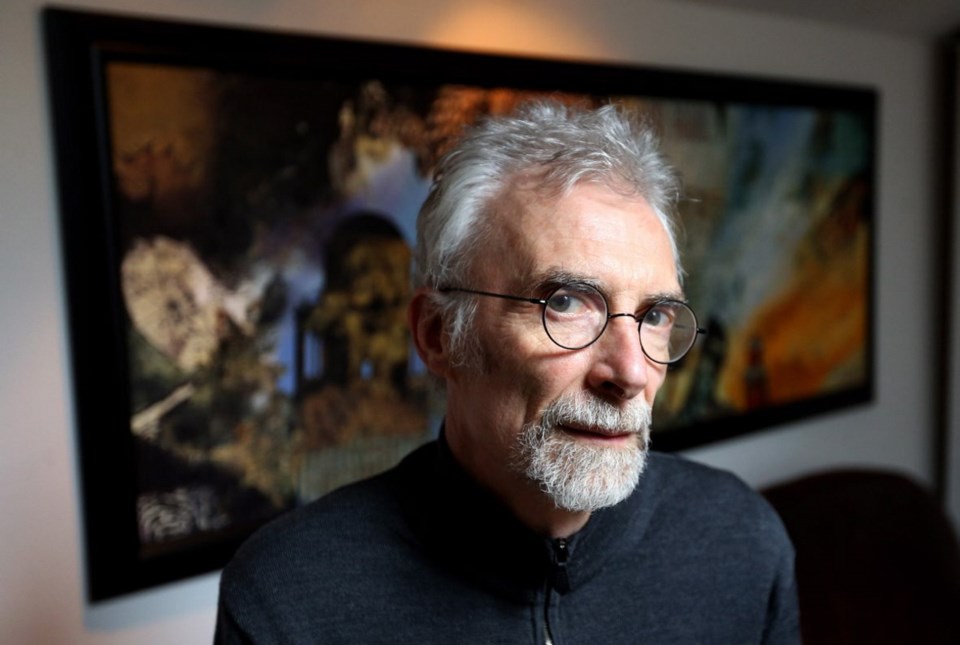

The silver-haired 64-year-old has a goatee, round spectacles and a quick, sharp wit. He’s an interesting fellow who once worked in an East End betting shop and designed a house inspired by Indonesian temples, a Russian orthodox church and an English cricket pavilion.

So who is this Trickster, anyway? Bantock believes he’s lurking within everyone’s psyche. Think of a rascal, or a mischief. A good example is Puck in A Midsummer Night’s Dream.

“What the Trickster does, he likes to tie your shoelaces together. He’ll knock your coffee cup off the table,” Bantock said.

This may sound, well … sort of annoying. But when it comes to the creative process, Bantock insists the Trickster is a useful ally, indeed.

For example, you might have a predetermined idea of how to write a short story or create a painting. Enthused, you pick up your pencil or paintbrush. Yet halfway through, you get stuck and can’t move forward.

In adults, such a creative blockage is typically caused by fear, Bantock says. Perhaps you think of grade school when your attempts to create were dismissed. You may worry your story won’t be as good as Alice Munro’s or Raymond Carver’s. Perhaps you’re worried you’ll create something silly or frivolous.

Allowing the Trickster to surface in the creative process knocks you out of “a predetermined way of working,” Bantock says. It means allowing yourself to rely on your instincts.

“I trust my playful enthusiasm in myself way better than the sense of ‘I know how to do this,’ ” Bantock.

He told a story about feeling blocked as a young artist in Bristol, doing mostly representational art that illustrated book covers.

“My work was very, very tight and it was getting tighter. I was holding my breath for eight hours a day,” he said.

One day, in desperation, Bantock, covered his wall in paper sheets. He grabbed some chalk pastels and daubed away for more than three hours. He didn’t try to create photographic realism; he just trusted his body, working from his shoulders.

When Bantock stepped back, exhausted, he was pleased with the effect. “It was like, ‘Whoa!’ ”

Allowing the Trickster to take over was a breakthrough — a liberating move that allowed a new richness into his artwork. However, this was only the beginning. Bantock figures it was another five or six years before he truly found a way of creating that reflected his true artistic self.

That said, it’s not enough to merely tap into an intuitive sense of play. Bantock doesn’t subscribe to “the 20th-century notion that if I call it art, then it is.” The serious artist, having tapped deeply into the roots of his or her creativity, must then apply critical judgment to what has been produced. And that’s where the hard work comes in.

Remember when writer Malcolm Gladwell suggested it takes 10,000 hours of practice to master a skill? Well, Bantock figures it’s more like 100,000 hours to achieve true mastery.

Bantock says he has two favourites among the 49 creative exercises in The Trickster’s Hat. One is called Building a Country. For this, you create an elaborate representation of the world that is “inside everyone of us” using a notebook, postcard, paints and collage materials.

The other is Travelling with Archetypes, in which you create an identity based on the archetypes of the Warrior, the Lover, the Healer … and of course, the Trickster.

As for the other exercises, well, you’ll have to buy the book.

Nick Bantock will be at Munro’s Books on Wednesday at 7:30 p.m. to speak about The Trickster’s Hat: A Mischievous Apprenticeship in Creativity. Admission is free.