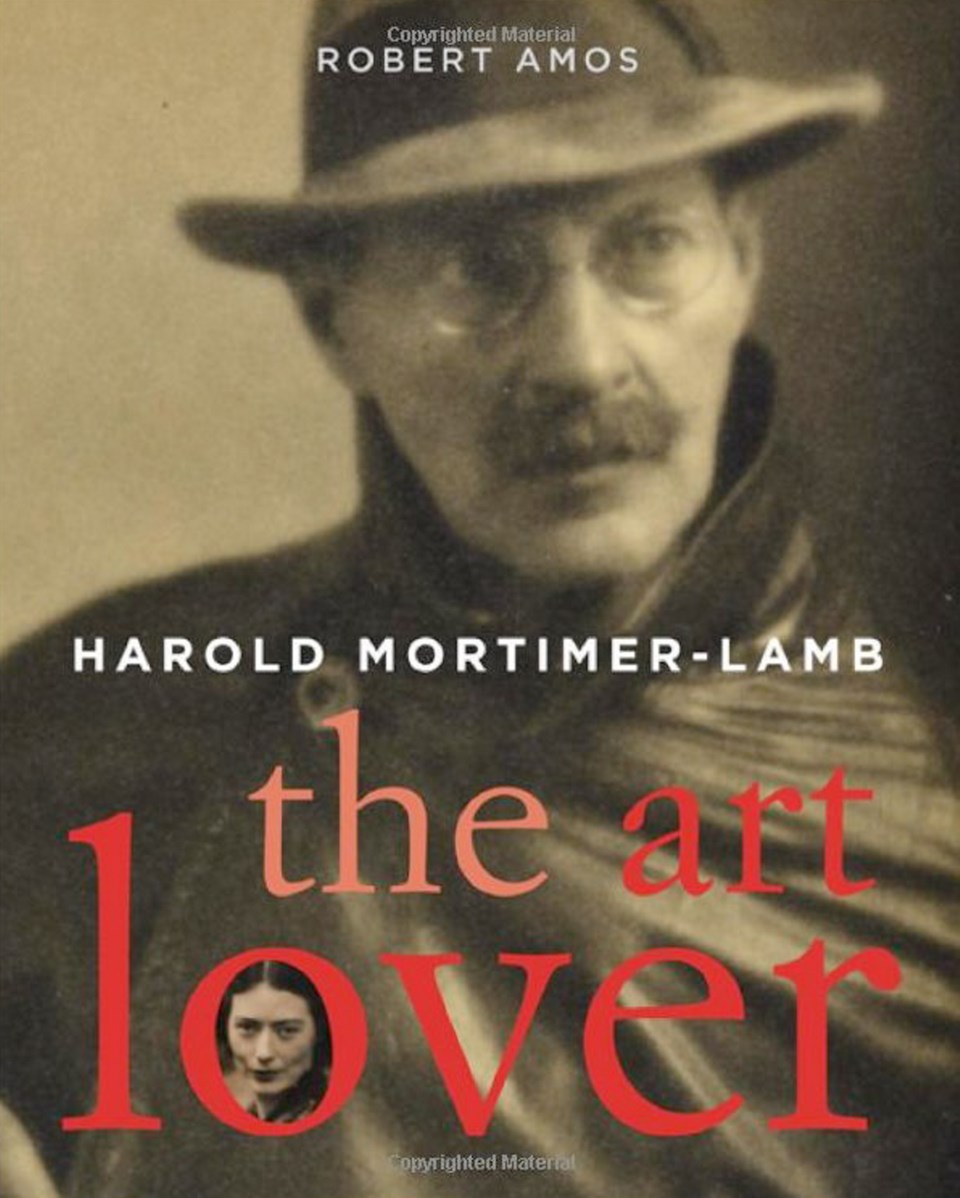

Photographer, writer, painter, promoter — Harold Mortimer-Lamb’s name appears in almost every Canadian art history book ever written, yet his place in the art world has never been easy to define. Illustrated with Mortimer-Lamb’s photos, paintings and the art he collected, this biography by local author Robert Amos brings into focus an unknown chapter in Canadian art history.

ROBERT AMOS

One day in 1978, Colin Graham, director emeritus of the Art Gallery of Greater Victoria, drove up to the gallery with a small moving van and proceeded to unload the estate of Harold and Vera Mortimer-Lamb. Scores of artworks were unpacked in the basement storage area; papers and photographs were carried to the library; household items were set aside for the volunteer committee’s Classy Cast-Off sale. A considerable amount of money was deposited in the bank for the purchase of Canadian art. I took a well-used Windsor chair from the van to my office upstairs and sat down to write about the donation for the gallery’s Arts Victoria magazine. That was my introduction to a fascinating story of love and Canadian art.

In stature, Mortimer-Lamb was small, with spectacles and a little goatee. With his first wife, Kate, he fathered six children, and at the time of her death they had been married for 45 years. During that time he also fathered a child by his housekeeper, Mary Williams, who lived with the family for the next 23 years. Their daughter is the artist Molly Lamb Bobak. Then, a widower at the age of 70, Mortimer-Lamb married the legendary beauty Vera Weatherbie, who was just 30, and they shared 28 years of happily married life, until his death at the age of 99.

Mortimer-Lamb loved art: the artworks, the people who made them and those who inspired them. He was a photographer, a painter, a patron and a promoter of art. He is mentioned in the index of many books about Canadian art history but —until now — has remained a figure in the background.

It was Mortimer-Lamb who first championed A.Y. Jackson, writing about him as early as 1911. It was Mortimer-Lamb who, in 1921, first brought Emily Carr to the attention of the National Gallery of Canada, and he was instrumental in bringing Frederick Varley to Vancouver in 1926, where he became his patron and supporter. Mortimer-Lamb was constantly in the company of the best artists — he befriended Sophie Pemberton in Victoria in 1904 and Laura Muntz in Montreal in 1907; he kept in touch with Arthur Lismer and the Group of Seven from the 1920s on and was at home to Jack Shadbolt in Vancouver from 1939. He was a neighbour of Lawren and Bess Harris. There are portraits of him by William Notman, John Vanderpant, Frederick Varley, E.J. Hughes, B.C. Binning, Fred Amess, Vera Weatherbie, Jack Shadbolt, Harry Upperton Knight, Joe Plaskett, Bruno Bobak and others. His photographs are in the collections of the Royal Photographic Society in London, the National Gallery of Canada, the Vancouver Art Gallery and the University of British Columbia. In the end, he and Vera left a collection of art numbering 192 pieces in every curatorial department in the Art Gallery of Greater Victoria. The British Columbia Archives holds more than 260 of his photographs.

Mortimer-Lamb was an exponent of what was called Pictorial photography, a soft-focus esthetic tinged with soulful symbolism. In the 1920s, Pictorialism was superseded by the hard edge of Modernism, at which time Mortimer-Lamb’s considerable achievements were deemed passé. Yet in the first years of the 20th century, he was the leading artistic photographer in Canada. His work was regularly exhibited and published in London and New York, and he was the Canadian correspondent for the leading art and photography journals.

Why is he not better known?

Mortimer-Lamb was not a tortured romantic soul. During his entire working life, he was fully and usefully employed by various divisions of the Canadian Mining Institute, and so was able to support and encourage the arts with his own resources. Thus he has been seen as a dilettante. As this story shows, he was not a trifler, but a man with a lifelong and profound commitment to art.

For 50 years, Mortimer-Lamb was involved with Vancouver’s galleries and museums, as founder, board member, donor and champion. In the end, he felt that his contributions would be more effective in Victoria, where the Art Gallery of Greater Victoria showed a serious interest in his vision. Building on the basis of his donations, that gallery’s collections of Asian art, decorative art, and Canadian painting have given it unique strength. Thus, he is better known in Victoria than Vancouver.

I took up the story of Mortimer-Lamb because I wanted to learn about his life. Why was Kate sequestered in the back room? What went on between Mortimer-Lamb and Mary Williams? Was Vera really Varley’s lover? How did the old codger catch the almond-eyed beauty?

In the end, Mortimer-Lamb took up painting dreamlike songs of joy and lived to be 99 years old. It was a wonderful life. How did he do it?

The simple answer seems to be — he was an art lover.

Excerpted from Harold Mortimer-Lamb: The Art Lover, TouchWood Editions ©2013 Robert Amos