PREVIEW

What: Paul Watson book launch (talks and signing)

Where/when: 2 p.m. to 4 p.m. today at the Maritime Museum of B.C.,634 Humboldt St., and 7 p.m. to 9 p.m. at Munro’s Books

Admission: Free

According to Inuit legend, a dead man was discovered in the Arctic more than a century ago in the darkened cabin of a marooned ship.

The body supposedly sat upright with a big smile on its face. Could it have been Sir John Franklin, the leader of the 1845 Franklin expedition in search of the Northwest Passage?

The “smile” might have been the sort of rictus grin one sees on corpses after lips and gums recede, says Vancouver writer Paul Watson. That is, if the tale is true.

“The hard part can be figuring out what are the good stories and what are the bad,” he added.

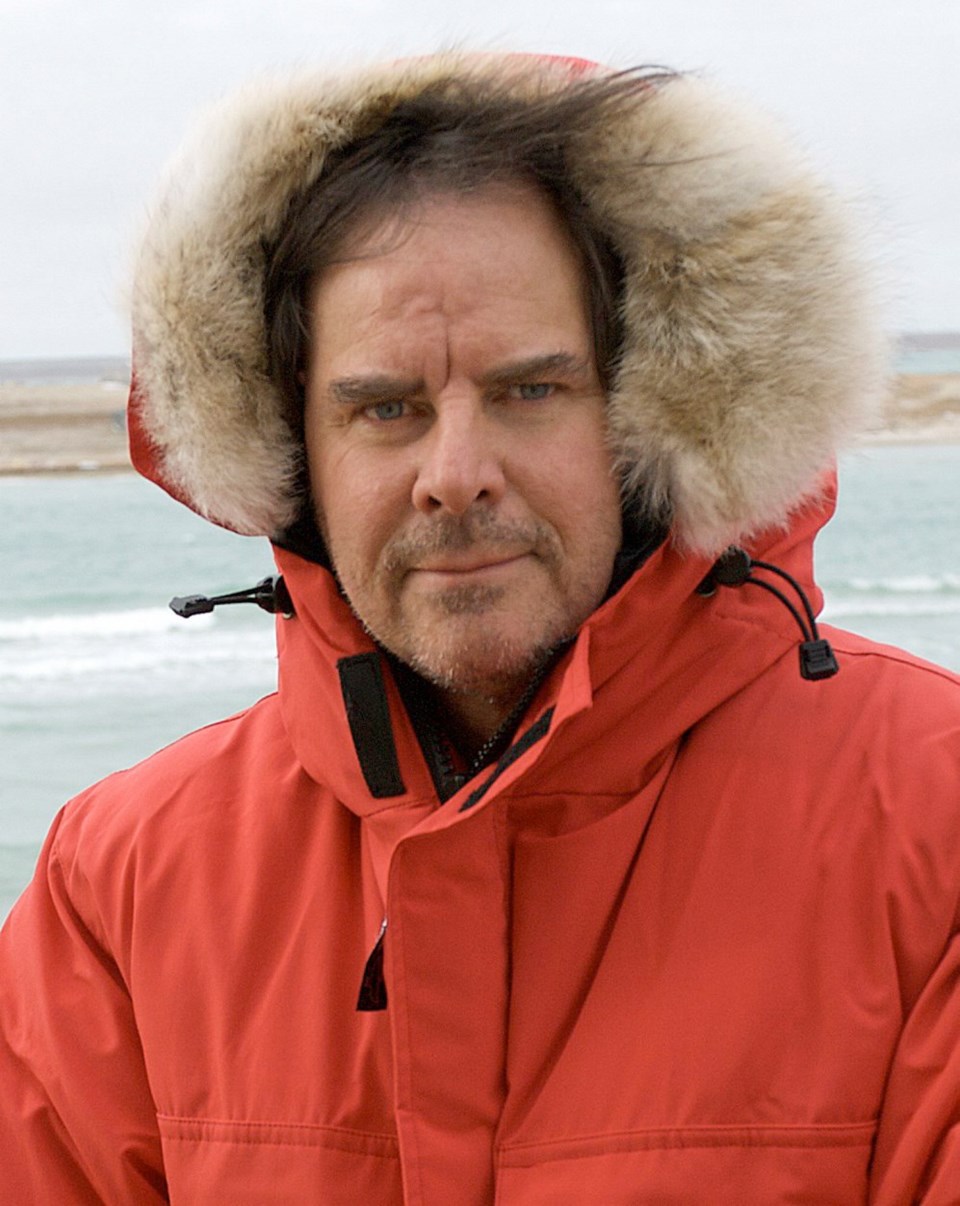

Watson, the author of Ice Ghosts: The Epic Hunt for the Lost Franklin Expedition, visits Victoria today to speak about his new book. It delves into the history of the expedition, as well as contemporary accounts of the search, ranging from Inuit lore to the findings of scientists and researchers.

The winner of a Pulitzer Prize for photography, Watson is a reporter who joined a 2014 expedition that found one of Franklin’s two lost ships, HMS Erebus. He subsequently broke the news of the discovery of the second ship, HMS Terror, in 2016.

These breakthroughs followed years of fruitless searches for Franklin and his 128-man crew, who disappeared in the 19th century without a trace. At the time, the mystery of the lost British adventurers gripped England’s imagination, providing fodder for sensational newspaper accounts. Thirty-six search expeditions were dispatched between 1847 and 1859 alone — all returning empty-handed.

Watson, who covered the Arctic for the Toronto Star, was the sole reporter on the expedition that found the Erebus. The veteran war correspondent (he’s reported on conflicts in such countries as Rwanda, Iraq and Afghanistan) admits he held no high hopes upon accepting the assignment.

“I wasn’t expecting to find anything. I thought it’d be a summer cruise and I could read a few books,” he said.

In Ice Ghosts, Watson writes about the first underwater images of the Erebus that appeared via sonar three years ago.

“The ship was firmly on her keel, proudly upright amid hard-packed flat cobblestone, gravel and sand, in just 36 feet of water. … Apart from a large bite out of the Franklin wreck’s stern, she was in remarkably good shape. … There was no doubt the long Franklin ship hunt was over.”

Naturally, Watson was keen to break this international story. However, Parks Canada, which led the expedition, strictly controlled all scientific data collected. Those aboard the ship had to obtain formal permission to communicate with the outside world

In fact, Watson learned about discovery of the Erebus three days after the sighting. A government PR person slipped into his cabin to tip him off.

“She literally whispered in my ear: ‘We’ve found a Franklin ship.’ But she said: ‘You can’t tell anybody.’ My initial thought was: ‘Holy s---, I’ve got a global exclusive but I can’t do anything with it.’ ”

By the time he was permitted to email his report a few days later, the CBC television had already broken the news. Watson still isn’t sure how the corporation navigated bureaucratic channels to accomplish this.

“Maybe someday I’ll find out,” he said with a chuckle.

In Ice Ghosts, Watson pays considerable attention to handed-down Inuit tales about the Franklin expedition, some of which turned out to be remarkably accurate. One of the more colourful characters he encountered was Louie Kamookak, an amateur Inuk historian who spent years interviewing elders and comparing their stories with books on the subject. He kept a portable library “crammed with a stack of old photographs and binders full of notes chronicling Inuit oral history.”

Kamookak collected tantalizing stories about Inuit people finding what might have been Franklin relics, such as butter knives and rifle ammunition. There were also tales of encounters with the survivors. The Inuit even had a good idea about where the wrecks were located.

Based on his research, Kamookak believes some survivors of the expedition might have walked out of the Arctic tundra, reaching more southerly areas with grass and flowering sedge. If so, they must have died before reaching the nearest outpost, Watson writes, adding: “Traces would be very difficult to find today.”

Another striking character in Ice Ghosts is Jane Franklin, John Franklin’s wife. It was Jane who had pushed her husband to undertake the expedition to find the Northwest Passage. She believed this would redeem Franklin’s reputation, which was tarnished following a controversial stint as governor of Tasmania.

When her husband (who was almost 60) failed to return from the Arctic, Jane lobbied obsessively to have search expeditions sent out. Convincing the authorities wasn’t easy. Franklin and his party had departed with three years’ worth of provisions, so the powers-that-be believed there was no rush.

In researching the book, Watson was especially intrigued by Jane’s efforts to contact her husband through seers and clairvoyants, who were in fashion at the time. Supposedly, the spirit of a girl, nicknamed Little Weesy, delivered a spooky message on the whereabouts of lost Franklin ships. Remarkably, one of the locales Little Weesy named, Victoria Strait, later became a focus of the recent Franklin search.

“You can just feel the obsessive kind of love that [Jane Franklin] must have had for her husband,” Watson said.