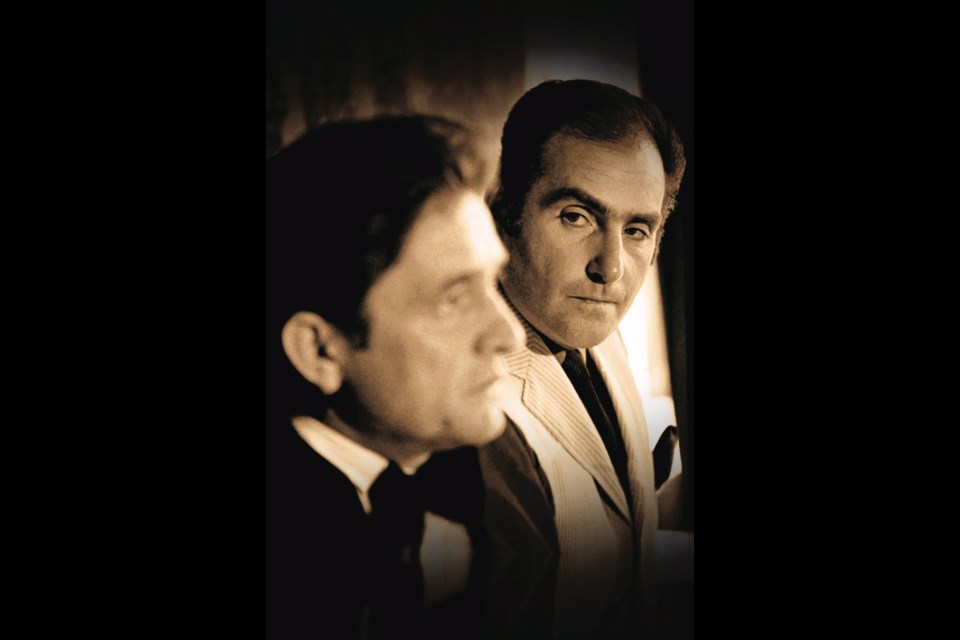

Few realize it, but the man who made Johnny Cash a superstar lived quietly in Victoria for years. That was Saul Holiff. Long forgotten by most, the music manager’s career recently gleaned international notice, thanks to Nanaimo journalist Julie Chadwick. The author of The Man Who Carried Cash (Dundurn, 392 pages), she has been interviewed by Fox News, Britain’s Daily Mail and other global news outlets.

The London, Ont.-born Holiff retired to Victoria and lived here for more than 15 years before his death in 2005. Chadwick says he was instrumental in propelling Cash from a country-and-western singer to a global phenomenon.

A relentlessly driven Holiff achieved this by dreaming big. It was he who scored Cash his own TV show. It was he who landed gigs at Carnegie Hall and Paris’s Olympic Theatre. His notion was to boost Cash’s career by presenting him at prestige venues that normally didn’t host country music.

“This kind of thinking was pretty ahead of its time,” Chadwick says.

Helping make Cash a household name was a tremendous achievement. At the same time, her biography makes clear that managing the singer — for years a drug-gobbling wild man — was a task of Sisyphean proportions.

For instance, the Carnegie Hall show turned out to be a write-off thanks to Cash’s amphetamine use (his addiction ultimately escalated to 100 pills and a case of beer daily). Drugs reduced his voice to a whisper. And Cash ended up blowing off the Olympic Theatre gig to hang out with Bob Dylan.

A devastated Holiff drank a bottle of scotch and resigned — only to be persuaded to return by Cash a few weeks later.

Holiff, who was Cash’s manager from 1960 to 1973, died by his own hand in Nanaimo. He was 79. His death by vodka, pills and self-asphyxiation is graphically described at the beginning of The Man Who Carried Cash.

Chadwick was a cub reporter at a Nanaimo newspaper when she first encountered the Cash/Holiff story. She had interviewed Holiff’s son, Jonathan, about a documentary he had created about his father. Jonathan then revealed he had access to a storage locker full of memorabilia chronicling Saul’s career.

This meticulously assembled trove contains 600 items, including letters, posters, photographs, telegrams and 60 hours of Holiff’s reel-to-reel audio diaries and tape-recorded conversations with Cash. (The Holiff family has since donated the collection to the University of Victoria library’s archives — the university will make a formal announcement this spring.)

Chadwick realized much of this material on Cash — a seminal figure in country and popular music — had never seen the light of day. This occurred to her while gazing at a photo of Cash (who turned to religion later in life) being baptized in a river.

“I was looking at the picture and it hit me. I was like: ‘This is a really big story. He just has this in his scrapbook. Has anyone even seen this photo?’ ”

At first, Chadwick wondered whether the story of a music manager warranted a full biography. She soon decided it did. It has historical importance, given Holiff was a key figure in Cash’s career. On top of this, Holiff — in many ways as mercurial, intense and conflicted as Cash himself — was a fascinating person in his own right.

“The more I dug into it, the more interesting Saul became, to the point where I thought he is actually as interesting as Johnny as a character,” Chadwick says.

Before he became Cash’s manager, Holiff — who carried a cash-stuffed suitcase adorned with a Canadian flag decal — was a rock-and-roll promoter in London, Ont. His company, Volatile Attractions, booked such stars as Sam Cooke, Buddy Holly, Duane Eddy and Carl Perkins.

At a London concert during the late 1950s, Holiff saw Cash give a sexualized, panther-like performance. He was favourably impressed.

Chadwick writes: “As an onstage presence, Johnny’s enigmatic electricity was unmistakable, and to see him was an experience that far surpassed his recorded material. Though still uncertain of himself, he commanded the stage in a manner that made it hard to look away.”

The Canadian music promoter had the vision to realize Cash had the potential to be a massive crossover star. He decided to offer his managerial services to Cash, who accepted.

Yet despite his boldness and big promises, The Man Who Carried Cash reveals Holiff as an insecure man who secretly questioned his ability to make good.

“He said: ‘I always felt I never deserved to be his manager, that’s as close to the truth as you’re going to get from me,’ ” Chadwick says.

Holiff reveals his self-doubts on hours of audio diaries, in which the clink of cocktail ice cubes is clearly audible.

“He was brutally hard on himself. There’d be times when I’d be listening to his diaries and I think: ‘Oh my God, give yourself a break.’ ”

Despite this, Holiff guided Cash through many important goal posts in his life, both professional and personal. When he decided Cash needed a “girl singer” in his act, it was Holiff who suggested June Carter. She not only became the love of Cash’s life but helped navigate the singer away from booze and drugs.

Overseeing Cash — one of the most riotous personalities in country music — proved to be a day-and-night job. Years before the Who and the Faces perfected the practice, Cash and his bandmates were trashing hotel rooms. They tossed furniture from balconies, painted doors, smashed down walls and staged “gunfights” in hallways with Colt .45s.

Meanwhile, Cash’s drug use became a thing of legend. In 1965, he was arrested for trying to smuggle 669 dexedrine tablets and 475 tranquillizers over the Mexican border. Cash would pound on people’s doors at 4 a.m., shouting for drugs. During one concert in Toronto’s O’Keefe Centre, the pill-addled performer stumbled out on stage and faced the wrong way.

During this period, he was found unconscious and without a pulse in his motorhome. Not knowing whether his client would live or die, Holiff drove Cash to his next gig in Rochester, New York. Cash not only revived, he went on to give “two clear-headed, sensational, sold-out shows.”

Although he, too, enjoyed a drink, Holiff was a serious-minded, hard-working man who preferred jazz and classical music over country. The man who toiled in scrapyards as a youth fancied himself something of an intellectual. Holiff took vocabulary-improving quizzes in Readers’ Digest and later earned a history degree from the University of Victoria.

During his career, Holiff was occasionally the target of anti-Semitism. Cash’s bandmates sometimes teased him for being Jewish. Holiff ultimately parted ways with Cash after June Carter criticized him for not attending their Christian concerts for the Billy Graham Crusades.

“Do you have something against Jesus?” said Carter, who hinted Holiff was interested only in money. It was the last straw — Holiff gave his five months’ notice.

Yet despite frequent fights and differences, a genuine affection existed between Cash and Holiff, says Chadwick.

“When it didn’t go well, you had these separate, very forceful personalities that clashed. But when it did go well, they were super complementary. Saul had all the Ts crossed and the Is dotted. And Johnny had this whole appealing charisma and his way of singing and presenting himself,” Chadwick says.

“Saul had this quality. He walked into a room and kind of saturated the air. A lot of people described Johnny Cash the same way.”