It’s no secret that Victoria is teeming with the paranormal — spirits are said to haunt every neighbourhood. But what some Victorians might not realize is that the whole of Vancouver Island, from tip to tail, is imbued with supernatural energy. In his new book, The Haunting of Vancouver Island, Island author Shanon Sinn transforms 25 of these legends — such as Oak Bay’s Woman in Chains, Nanaimo’s axe-murdering Kanaka Pete and the Ahousaht Witch — from dubious gossip to well-researched accounts. The result is a compelling investigation into supernatural events and local lore from every corner of Vancouver Island.

• • •

Fort Victoria was built in 1843, on the southernmost tip of Vancouver Island. The island was a rough place at the time, inhabited by colonizers, fortune seekers and First Nations people.

When the fort was founded, officials declared that it would serve more than just one purpose: Borders were still in flux following America’s independence from the British Empire, so its placement was primarily strategic. The fort’s presence would declare to foreigners and to native-born alike that Vancouver Island belonged to the British Empire. The Hudson’s Bay Company (HBC) would spearhead the project. It had been granted the rights to Vancouver Island’s resources for 10 years, with the explicit condition that it helped Britain colonize it. For this purpose, the fort would also establish a permanent harbour for resource exploration and serve as a company trading post to resupply inland outposts, as well.

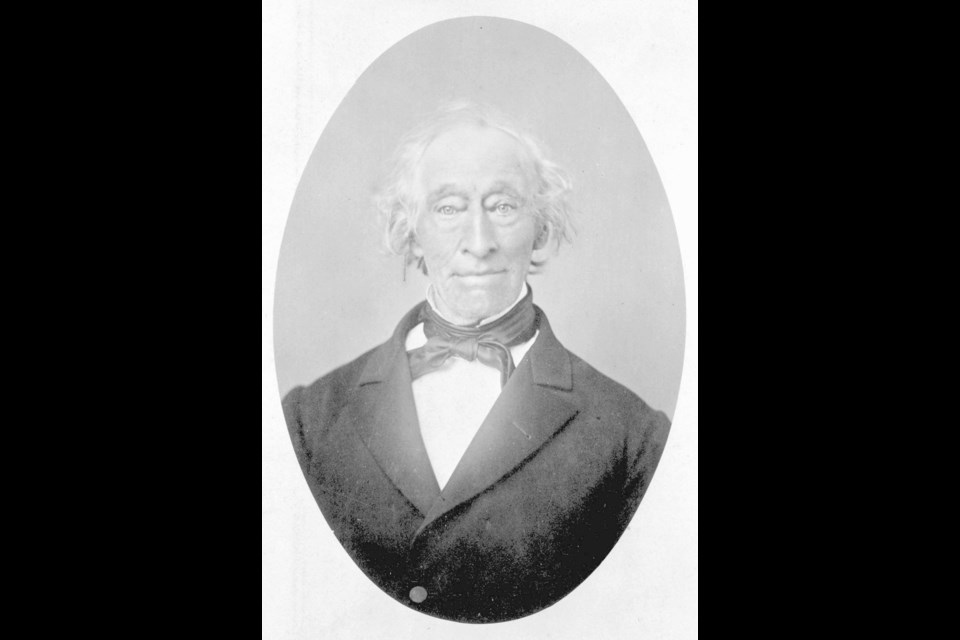

According to the online Dictionary of Canadian Biography, John Tod was a fur trader for most of his life. Born in Scotland, he immigrated to Canada in 1811 as an employee of the HBC. At 56, he came to Vancouver Island looking for a place to settle. Most of the early homesteaders on Vancouver Island were Hudson’s Bay Company men who had been rewarded with land for their services.

Tod had been married more than once before he settled in Victoria and already had several children. He arrived at Fort Victoria with Sophia Lolo — a woman of mixed First Nations ancestry — who is believed to have given him seven more children. They were not formally married until 1863 after one of Tod’s former wives passed away.

Tod’s was a large rural parcel he intended to use for farming until he retired. As this was long before Oak Bay became a part of the Greater Victoria area, his land was over a hundred acres and reached out toward the rocky shoreline. When the Tod House was first built in 1850, there were only a few hundred white settlers in the Victoria area, some coal miners at the north end of the island at Fort Rupert and a handful of settlers elsewhere.

The house — now the oldest standing home in British Columbia — was built facing the Chatham Islands. Coincidentally, it’s close to Victoria Golf Club, as well.

Upon his arrival, Tod was nominated as one of Vancouver Island’s first legislative council members, a position he held for several years. The Dictionary of Canadian Biography records indicate that he was well read and musical, but also that others considered him “vulgar” and “not generally liked.” During the period before his death in 1882, Tod was openly involved with the spiritualist movement — a practice that allowed communion with the dead. He was known to have participated in séances.

Reports of the Tod House being haunted begin as early as the 1920s. The one-storey structure is now unassuming compared to many of Victoria’s large older homes, but its reputation brought it renown throughout the province. By the late 1940s, so many people had witnessed activity in the building that several newspapers reported it, and the CBC aired a story.

In 1949, the Daily Colonist reported unexplained activity, such as cabinets opening on their own, objects moving and a biscuit barrel suspended on a hook that would sometimes “swing” for hours. During one Christmas season, all of the decorative holly on the walls was taken down and thrown into the middle of the room. The cellar door was also seen opening by itself by several witnesses.

In Ghosts: True Tales of Eerie Encounters, Robert Belyk said that one owner of the home — Mrs. Turner — would later claim she would wake up in the middle of the night with a feeling that someone was in the room with her. Additionally, her cat would sometimes hiss, growl and arch its back for no reason. Mrs. Turner often felt as if someone were walking behind her. She would later say that neither she nor her daughter would spend the night in the master bedroom alone, as it gave them an unsettled feeling.

The Daily Colonist reported that Lt.-Col. T.C. Evans and his wife purchased the home in the 1940s. Mr. Evans told the paper that he was “never much disturbed by the manifestations.”

During the war the couple had gotten into the habit of inviting serving military personnel to stay during their weekend leaves. Mrs. Evans put two of the men into the old master bedroom for the night. In the morning, the room was empty. The men had fled.

When the servicemen returned, they spoke of a horrific night. Most startling of all, one of the men claimed to have seen an apparition in detail.

The man awoke with an ominous feeling. There was a sense that he was not alone. He remembered having heard the sound of rattling chains. Half asleep, the guest peered into the darkness of the master bedchamber.

Hard eyes glared from out of the inky blackness. Accusing. Unblinking. A bedraggled woman stood in the shadows. Tangled hair twisted across her face and down her shoulders. Her arms slowly stretched toward him with curling grasping fingers that danced in unison. There were iron bands around her wrists and ankles.

He watched wide-eyed from his bed, completely paralyzed and unable to move.

The figure appeared to be First Nations. Her eyes were sad and pleading. Long black hair framed her face like a cape of darkness. She reached for him. Closer. Her mouth forming words he could not hear.

Then, she was gone.

When the guest grabbed his belongings and fled, the other man, just as terrified, followed behind. It is not known if he saw the apparition, as well.

According to Belyk’s account, Mr. Evans hired contractors in 1947 to help him with some much-needed renovations. One of the projects was the addition of a furnace near the front of the house. While digging a deep pit for the equipment, the contractors came across the corpse of a woman in chains. She was believed to have been one of John Tod’s wives.

The Daily Colonist reported that an anatomist was called in who said the body had been soaked in lime. Most terrible of all, the woman’s head was missing. It was determined that the body was likely an Asian woman, though it was difficult to say for sure. Her bones were so badly decomposed that they crumbled when they were touched. Daily Colonist stories that followed claimed the activity in the house ceased with the removal of the body.

Some modern versions of the story have claimed that the haunting activity actually increased. This is not true. In 1949, Mr. and Mrs. Evans told the Daily Colonist that the activity ceased when the body was taken away. The reporter said he had the impression they missed the ghost. When asked if she had ever been afraid, Mrs. Evans told him that she was “always more frightened of newspapermen and researchers than of manifestations from the spirit world.”

Excerpted from The Haunting of Vancouver Island: Supernatural Encounters with the Other Side, TouchWood Editions © 2017 Shanon Sinn