The following is excerpted from Zhindagee: Selected Stories of Our First Daughters, by Mahinder Kaur Doman Manhas.

The oral history and contributions of many (Asian) Indian pioneers has largely remained undocumented by authentic sources, thus mostly excluded from formal studies.

The history of pioneer (Asian) Indian women in the 20th century has been somewhat overshadowed by other historical incidents pertaining to immigrant Asian Indians. The exclusion of these women, practised by the governments of the time, left gaping holes in the family lives of many men who came here to make a living and build a new life.

An abundance of photographs, which have surfaced over the past 150 years or so, were taken of unidentified Indian immigrant men in the 1800s and early 1900s. The photographs pose many unanswered questions.

Who were these immigrant men? Where were these photographs taken? By whom? How did the men come here? Did they come alone or in a group? What was their contribution to British Columbia? To Canada? Did they have families in India? Where are the descendants, if any, now? How did the exclusion of Indian women and children affect those unidentified men?

After the First World War, the Imperial War Conference permitted the legal entry of Indian women to Canada. Many first daughters and first sons of these pioneer families have now died. Many of those who remain are elderly and in frail health.

Their generation is slowly slipping away, mostly without recognition and without documentation of their histories. If at all, their presence has mostly been captured through traditional oral family history and/or minimal documentation. Their presence and contributions to the fabric of British Columbia and of Canada are noteworthy to better understand the Indian Diaspora.

Asian Indians in British Columbia are relatively recent immigrants. The earliest recorded history of their presence dates their arrival around the mid-1800s when merchants, sailors and mercantilists briefly sojourned.

As time passed, retired Sikh soldiers came to view the reported beauty and vastness of the British Empire’s newly settled colony as they travelled to India after attending Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee celebrations. These travellers sent inviting reports on Canada and its prospective wealth to their friends and relatives.

Around the same time, some steamship companies, particularly the Canadian Pacific, stirred up interest in emigration to Canada among the people of the Punjab.

According to Hugh Johnston, the author of The Voyage of the Komagata Maru, the Sikhs in 1904 were “encouraged by Hong Kong agents of the Canadian Pacific Railway who were seeking to replace steerage traffic lost after the Canadian government had raised the head tax on Chinese immigrants.” Slowly, and sometimes in small groups, men who were assumed to be “Hindu” arrived in British Columbia.

Early in the 20th century, working-class Sikh men came to Victoria and Vancouver. Some eventually came to Paldi, a few kilometres west of Duncan. They temporarily left behind them their families and friends in the Punjab, an agricultural area in the northwest of India, bordering on present-day Pakistan.

Mainly these pioneers came from India for the opportunity to earn more money than they could earn in India. Others who were adventurous simply wanted to make a new home in a part of the British Empire that promised no forms of discrimination.

At that time, Indians from the diaspora were not known to immigrate to Canada.

However, British Columbia, even though it was part of the British Empire, did not welcome 258 Asian Indian men in 1904. Much to the dismay of the immigrants, overt anti-Asian feelings were conspicuous.

According to Samuel Raj, “local politicians denounced the East Indian immigrants as a burden to the city” and proclaimed that they were “destructive of the British way of life in the province… and breeders of disease.”

Newspapers in both Victoria and Vancouver “maligned” the Sikhs. In sensational language, press captions urged action to restrict Indian immigration: “Get rid of Hindus at whatever cost.”

Although the anti-Asian feeling was overt, Indian immigration continued slowly but decisively, restrained only indirectly by immigration laws.

A “Continuous Voyage Order,” originally to prevent Japanese from immigrating to Canada from Hawaii, affected Indian immigration. The Order of Council said that “the Governer-General in Council may … prohibit the landing … of any immigrants who have come to Canada otherwise than by continuous journey from which they are natives.”

Indians could not comply with the order since no steamship companies provided direct service from India to Canada. To prevent a court challenge, a new Immigrant Act was introduced in 1910. In its terms was an order that all Asian immigrants, with the exception of the Japanese and Chinese, had to have $200 with them when they disembarked in Canada.

Later, a regulation to stop the arrival of skilled and unskilled labour affected the Sikh community.

Despite these setbacks, around 1910 many Indian men had decided to settle permanently in British Columbia, so they began to discuss the coming of women and children from India.

A great deal of conflict with the larger society arose around the issue that took almost 15 years to resolve. White Canadian society took the position that two wrongs did not make a right: since the admission of Indian males had been wrong, the admission of women would not right the situation at all.

In the newspapers, it was put this way: “[For] the comfort and happiness of the generations that are to succeed us, we must not permit their women to come at all.”

Clearly, it was hoped that the men who wanted families would return to the Punjab or else remain in Canada without fathering successive generations. Perhaps, it was an opinion that only Caucasian women would build stable families for British Columbia.

By 1910, three of the Sikh elite had wives with them. Nothing is written about the women in their own right. Instead, they are noted in passing:

“Mrs. Sundar Singh and Mrs. Teja Singh came to Canada with their husbands. Mrs. Uday Ram Joshi arrived on February 10, 1910, and was admitted having fulfilled the requirements.”

Both Teja Singh and Sundar Singh had been trained at India House in London, England so they were no strangers to British public opinion or mores.

In July 1911, Hira Singh returned from India with his wife and child. Hira Singh was permitted to enter, but his wife and child were held for deportation. As the immigration ban had been overturned in the case of Bhag Singh and Balwant Singh, it was reported again, after a vigorous protest from the Indian community.

Mrs. Hira Singh and her three-year-old child became another exception to the immigration ban.

Allegedly, Mrs. Hira Singh gave birth to another daughter on June 12, 1912. No written documentation of the birth has been found, and if it is valid, the child would be the first daughter of Indian descent born in Canada.

There is no known oral history or documentation on the whereabouts of Hira Singh’s daughters, the life of her mother, and/or their descendants. If this snippet of rare history is correct, it begs many questions. Did the mother have relatives? If so, who and where are they? Did the daughters survive to have families of their own? If so, where are they now? Is there documentation which has not been revealed?

Late in 1910, two priests returned to India to bring their wives and two small children to British Columbia. However, the coming of the wives was not a matter of course. Instead, they arrived in Canada as an exception to the rule:

“Wives of Bhag Singh and Balwant Singh and their children arrived in Vancouver on January 22, 1912, with their returning husbands. The husbands were allowed to return to their homes as they had Canadian domicile but the wives and children were detained for deportation. They were freed on bail later. Their plight was taken up by the entire Indian community and their sympathizers … it became the object of many deliberations in several places in Canada as well as in London, England and New Delhi, India. After several months of uncertainty, the families’ nightmare came to an end with intervention by Parliament.”

Little is known about Harnam Kaur, wife of Bhag Singh, other than she was born at Peshwar, Punjab (now Pakistan) in 1886.

“She died in 1914 at her home in Vancouver’s Fairview district, nine days after giving birth to a daughter. On the day of her funeral, the Vancouver Sikh temple accepted responsibility for her daughter. Tragically, their father died in a shooting at the temple later that year. Because there were so few Punjab women in Canada, the baby girl was placed with a white woman (possibly Anne Singh, the wife of a Punjab Sikh). When she was six, the temple sent her to India for a Punjabi upbringing. There is no mention in the available records of the fate of her brother Jogindar Singh (birthplace Hong Kong) after their father’s (Bhag Singh) death…”.

Kartar Kaur, the wife of Balwant Singh, gave birth in August 1912 to the first known Indian child born in British Columbia, Hardial Singh Atwal. His family members still live in Duncan.

Although the Indian community unanimously supported the immigration of Asian Indian women, not many white Canadians agreed with them. Indian women, who were British subjects, certainly did not have the freedom of British Empire. They were more or less barred from Canada.

However, some people in Eastern Canada responded to Indian women’s plight and found support in British Columbia in Presbyterian minister Louis Walsh Hall and Isabella Ross Broad. Broad’s document “An Appeal for Fair Play for Sikhs in Canada,” published in Toronto in 1913, is noteworthy. A petition to the government in Ottawa was presented by Teja Singh (sant), Rajah Singh, Sundar Singh, and Hall.

These people, along with Dr. Sundar Singh, were responsible “for creating a favourable climate in university circles and clubs, such as the Empire Club and the Canadian Club.”

Dr. Sundar Singh’s speech and petition are both noted in Broad’s document.

Dr. Sundar Singh met in Victoria with Bessie Pullen-Burry, an activist, during her travels across Canada in 1911. He asked her “to represent the case of the Sikhs in [her] writings to the people of England.”

She did that on a page of From Halifax to Vancouver where she assured him of her “entire sympathy.”

His argument, in summary, was that many of them “were old soldiers of the Empire; they were faithful to the British Raj; and having acquired a sufficiency wished their wives to join them … he hoped, in view of the fact that the Sikhs were subjects of the Empire, this privilege would eventually be extended to them.”

Raj said “Hall and especially Broad made considerable impact on the church-going Christians,” but ultimately, they were not successful.

“Where it mattered most, west of the Rockies, even the Ministerial Association voted to keep the (East) Indian women out, lest a “Hindu colony” emerge in a Christian country.”

Furthermore, the National Council of Women also voted to keep out the Asian women.

Immigration officials had another way of making entry to Canada difficult for women. Lest more men return to India to accompany their wives to Canada in the hopes that clemency for their families would follow, the Immigration Department refused to issue the vary identity certificates, which men required to re-enter Canada.

They too challenged discriminatory laws. The famous Komagata Maru incident resulted in closing the door on Indian immigration to British Columbia. Johnston described the incident:

“In May 1914, 400 Sikhs left for B.C. by chartered ship, resolved to claim their rights to equal treatment with white citizens of the British Empire and force entry into Canada … anchored off Vancouver for over two months, enduring extreme physical deprivation, and harassment by immigration officials … defied federal deportation orders, even when the Canadian government attempted to enforce them with gun-boat … leaders of the group … were finally persuaded to return to India. They were then full of revolutionary fervor against the Raj.”

But the women’s case was to have a better hearing, at least officially. After years of facing contrived rules and policies fabricated to justify their exclusion, women were to be allowed to enter Canada. At the Imperial War Conference, 1917-1919, the Indian government secured an agreement which permitted Asian Indian women to enter Canada.

Following the agreement, however, only a few women entered. Nothing seems known about them. None came in 1920. Only eleven women and nine children entered in the years 1921 to 1923. Their histories are lost forever.

As more women entered in succeeding years, some of them joined their husbands in Paldi, a few kilometres west of Duncan. Many women were told by their husbands to leave their Indian clothing and jewelry in India, and the women adopted western styles of dress.

In the new settlement, community life was naturally structured to resemble village life in India. The women lived a very cloistered life and communicated with the larger society only through their husbands, and ultimately, their children. However, that was not all bad, since amongst the women of the community there was a strong familial interdependency and a fierce loyalty.

These women rarely associated with people of the larger society. They did not drive cars or enjoy individual mobility. The community members who were not family members became so over time. When children spoke of Massi Ji, Nanni Ji, the title was both literal and figurative.

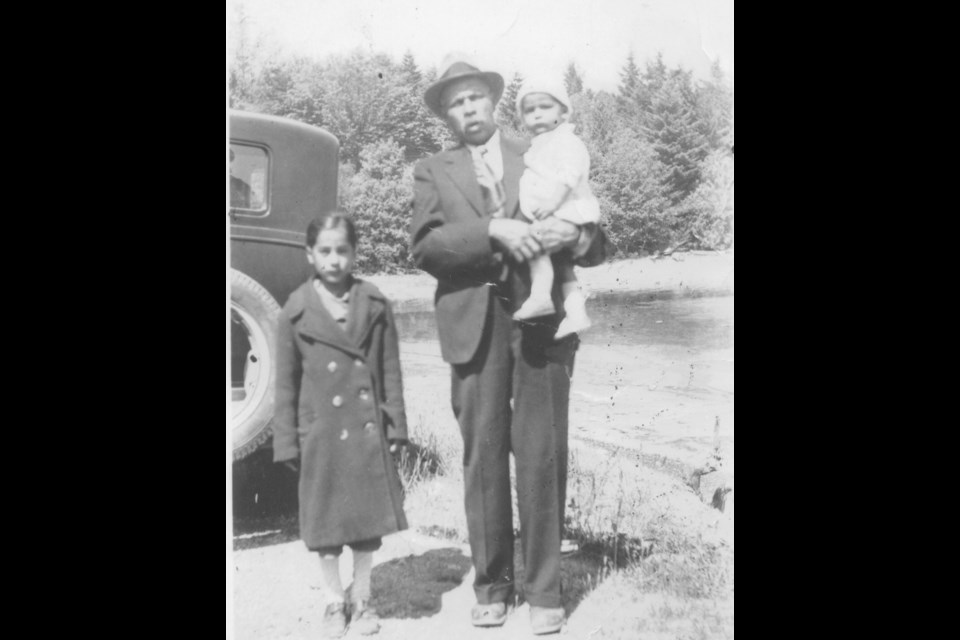

In 1930, Prabh Kaur, with her husband’s small nephew, the late Meetow Singh Manhas, joined her husband in Paldi. She was always extremely reluctant to talk about her life and her feelings in those early days in British Columbia.

Sustained by her Sikh religion and her community, she did was she had to do. She worked hard to feed her children, to look after the house, her husband and the neighbours. Thirty or forty others in Paldi did the same. She was willing to admit, however, that western-style food preparation made her legs ache. Accustomed to squatting on the ground at home in India, she had to stand to prepare meals in her new world.

As a child, I asked her why she did not speak English, and as an adult I asked again. She said she did not have the time to learn. Even if she had had the time, there were no classes available to her, she added. Besides, the men took care of “outside” things, so the new language was the men’s responsibility.

Since neither women nor men of the Asian Indian community had the right to vote until 1947, Prabh Kaur and others did not have the incentive of citizenship responsibility to motivate her. Other Indian women pioneers substantiated my mother’s observations and experiences.

Most of the women among the first “wave” of arrivals, from 1920 to 1950, have died. Mostly oral history has captured some of their observations about adapting to life in a province in which they knew they were unwanted. However, in their own community, the fight to have them in Canada took precedence over male political rights such as the franchise.

The history of the first daughters must be preserved. Otherwise, their existence in B.C. will not be charted well, and will fade with the passage of time.