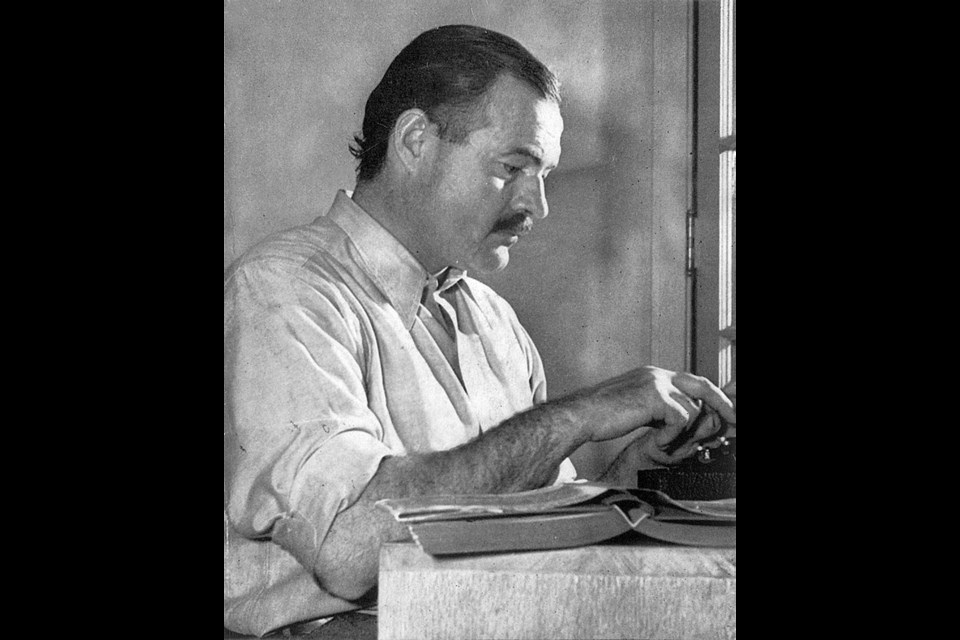

Ernest Hemingway: A Biography

By Mary V. Dearborn

Knopf, 752 pp., $47

A favourite short-story allegory of Ernest Hemingway challenges his readers, through the epiphany of a leading character, to examine a world that has lost all hope.

“Religion is the opium of the poor,” says a character of The Gambler, the Nun, and the Radio, a statement that sends Mr. Frazer — in reality, Hemingway himself — into a state of reflection.

Isn’t it true, Mr. Frazer retorts, that music is an opium of the people? Patriotism? Sex, drink, ambition, gambling or even his own radio?

Aren’t they all forms of “opium”?

Isn’t it true that one’s life can’t exist without support in one form or another?

For readers of a new Hemingway biography, it leads to a bugging question: What was Hemingway’s opium? Or, more to the point, what was lacking that he needed to sustain him through his darkest days, which ultimately led him to take his own life in July 1961?

It’s hard to say, but given today’s increased emphasis — and knowledge — about mental health and the workings of the brain, people still want to know about Hemingway.

Biographer Mary Dearborn is the first in 15 years to dive into the life of one of the most mysterious, complex and conflicted historical figures of the 20th century. She succeeds in providing the reader with a detailed study of the man known as much for his words as his robust, charismatic manliness and his efforts to buff that reputation and legend.

Dearborn takes the reader through a chronology of Hemingway’s life and work. In fact, it’s helpful to keep a book of his short stories nearby. She examines a number of his works and surmises Hemingway’s inspiration and true identity of characters.

Most interesting is the character study. Dearborn takes on Hemingway’s many shortcomings. Alcohol and adoration were his opium. Neither could sustain him, and the spirits were partly culpable in his many dark sides.

Dearborn tells of a Hemingway who was temperamental, at times violent, and terribly needy and sensitive. He tossed good friends aside — see F. Scott Fitzgerald — on a whim. She notes one observation that “as long as people around him were worshipful and adoring, why, then they were great.” When he believed they no longer were, they were gone.

It’s a character trait that Dearborn traces to Hemingway’s childhood.

It manifested itself in paranoia, and mental and emotional dysfunction as he aged, and it worsened, Dearborn believes, through traumatic brain injuries Hemingway suffered in adulthood. In all, Dearborn counts six concussions, including the blast in Italy during the First World War that hospitalized him for weeks, and airplane accidents in the 1950s.

These, Dearborn asserts, along with his alcoholism, were complicit in the increase of manic episodes that reached a peak as he concluded his sixth decade.

Hemingway, too, might have been predisposed through genetics or osmosis. Mental illness was a family trait. His father committed suicide in 1928. Two siblings later did as well. Hemingway’s granddaughter Margaux took her own life, and his son might have.

In fact, Dearborn notes, Hemingway acted just as his father had leading up to his suicide — deluded, irritable and distrustful, desperately dwelling on his finances and with an irrational fear about his taxes. He believed he was being followed and that his house was bugged.

One morning in April 1961, his wife, Mary, found him in a corner of the house in Ketchum, Idaho, near the gun rack with a shotgun in his hands and two shells nearby. He was sent back to the Mayo Clinic in Minnesota for more shock treatments. Those did nothing to alter his fate.