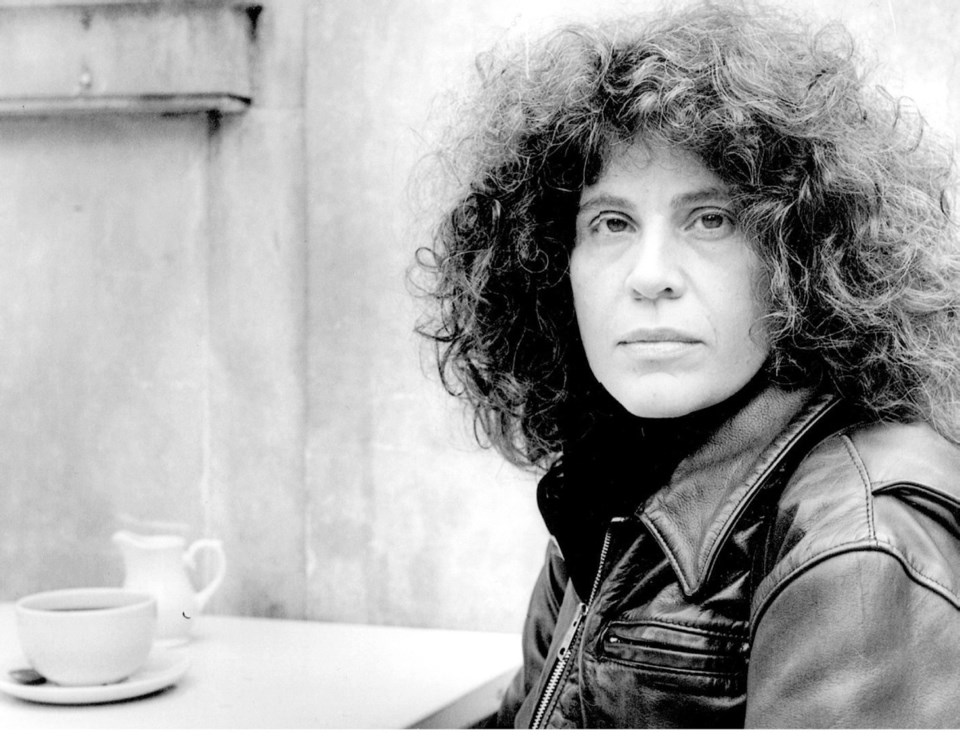

For many, fiction is pure entertainment. But for Anne Michaels, there’s both a power and responsibility that comes with the form.

As an author who grappled with difficult historical events like the Holocaust through her 1996 award-winning novel Fugitive Pieces, as well as the relocation of Egypt’s Great Temple at Abu Simbel in 2009’s The Winter Vault, Michaels sees fiction is a tool for understanding.

“The collection of facts is one thing. To discover the meaning of the facts is quite another thing,” she said in an interview. “Fiction allows you to communicate meaning in ways that one hopes would reach the reader in a particular and profound way.”

Speaking on the phone from her Toronto home, Michaels chooses her words carefully — pausing and releasing them slowly, rather than correcting herself later. She has been famously tight-lipped about her personal history, brushing aside journalists’ questions about her heritage and family life, so that those “banal details” won’t interfere with interpretations of what’s more important: her writing.

Though she began by writing poetry, Fugitive Pieces launched her into the international fiction spotlight, picking up awards around the globe, from the Guardian Fiction Prize to the Orange Prize. Anticipation built for 13 years before she released her second novel, 2009’s The Winter Vault. This novel shared the themes of memory and loss, covering historical events like the re-routing of water to create the St. Lawrence Seaway in Eastern Canada through the personal lens of characters involved.

Michaels will receive an honorary degree Monday from the University of Victoria, as well as giving a free President’s Distinguished Lecture at 7 p.m. She will talk about fiction’s responsibility in the lecture, which borrows its title from a line she wrote in Fugitive Pieces: “The mystery of wood is not that it burns, but that it floats.”

The line points to Michaels’ optimism and belief in resilience, in the face of some of history’s greatest horrors.

“It does signify to me a really profound kind of hope,” she said, reflecting on its meaning. “Hope or faith, in the general sense of the word, after the worst thing.”

Fugitive Pieces, she said, was an exploration of what that faith might be — what it would feel like, what form it would take. The story centres on a boy rescued from an archeological site by a Greek geologist, after Nazis murder his parents.

“We are very convinced of violence and the truth of violence. We don’t need that to be proved to us,” she said. “But we do seem to need proof of the power of compassion, of goodness. Things that we normally see as, in some ways, less powerful — sometimes powerless completely. And that’s part of the mystery.”

In approaching history, Michaels says she undertakes a rigorous process of research, spending years upon years examining facts, historic events, details. When it’s painful or horrifying, it’s a difficult process. But she’s committed to rejecting the first “answer or solution” she encounters in favour of digging deeper. Her goal is to take the incredibly complex events of history and give them some clarity.

“I never publish a book unless I feel that I can bring the reader — myself and the reader — to the other side,” she said. “So any assumptions, anything that I put forward, has been something deeply tested to its limit before I feel that it’s trustworthy to give to the reader.”

While Michaels has previously described the relationship between writer and reader as an “alchemy,” she said a book can never prescribe what readers should think or how they will interpret it. “What I can do is set forward certain ways of looking, certain ways of asking a question,” she said. “The answer, if there is an answer that I find … that’s for the reader to accept or not accept, to take in or not take in.”

Part of the truth or the answers that she encounters has to do with morality. There’s a freedom in fiction that allows for expressions of morality in a way that’s difficult to do in non-fiction. She once told the Guardian that the message of The Winter Vault was simple: It’s not enough not to do harm; one must also do good. That regret and shame are not the end of the story; they are its middle.

“The thing about fiction is it allows you to exercise that muscle of morality,” she said. “It allows us to examine, re-examine, to consider our actions, to reconsider our actions. You can turn back the page and experience again and try and understand again.

“History is very uncompromising about that. With fiction, we can enter and re-enter in a certain way.”

Tickets for Michaels’ lecture at the University Centre Farquhar Auditorium, Monday at 7 p.m. are free, but must be reserved in advance. Contact the UVic Ticket Centre: tickets.uvic.ca or 250-721-8480.