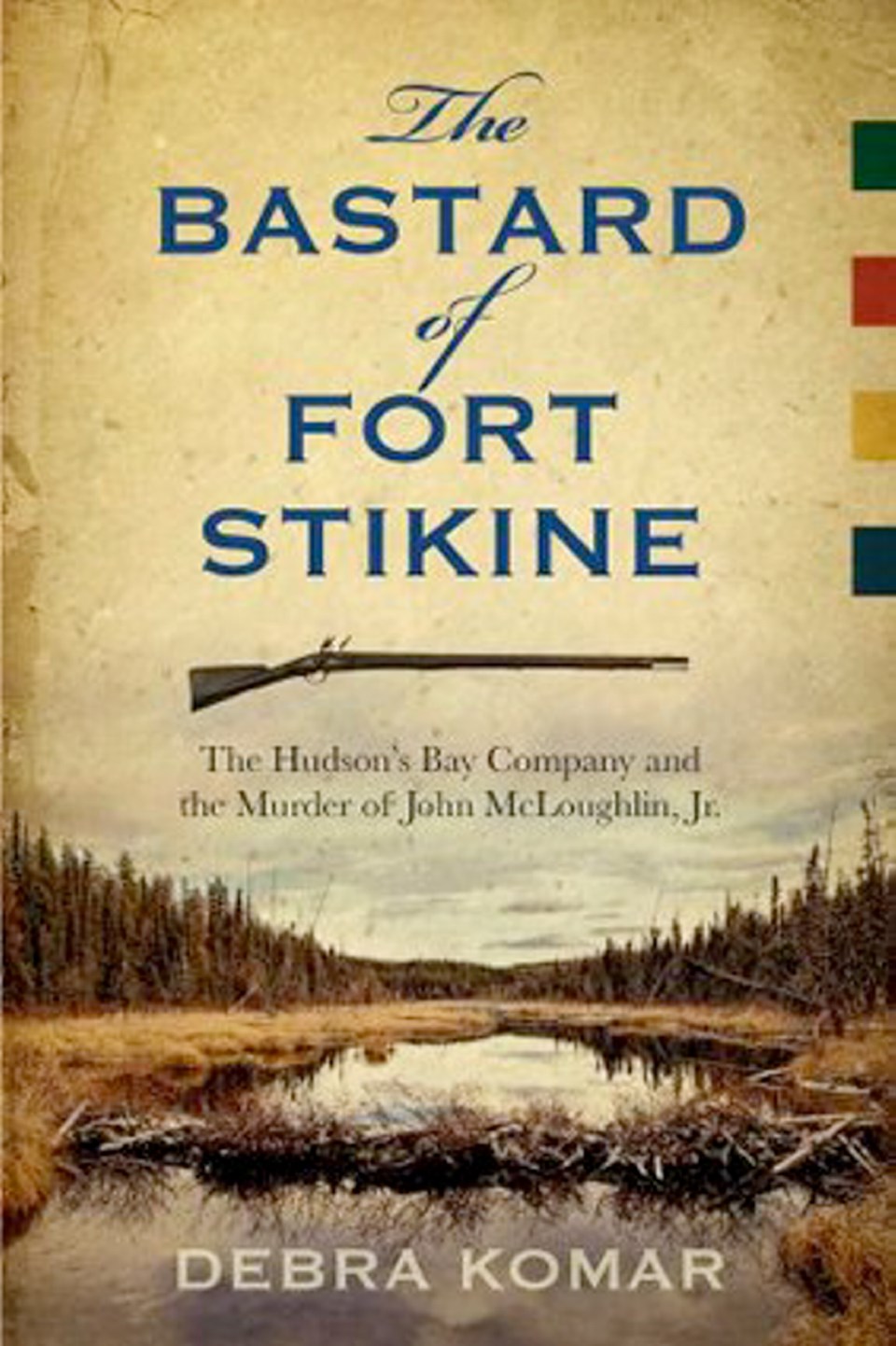

The Bastard of Fort Stikine: The Hudson’s Bay Company and the Murder of John McLoughlin Jr.

By Debra Komar

Goose Lane, 296 pp., $19.95

Fort Stikine was, briefly, a Hudson’s Bay Company outpost in Russian territory, on what is now the Alaska panhandle. The community of Wrangell has taken the place of the old fort.

John McLoughlin Jr. was the second chief trader at the fort, serving until he met his demise at the hands of the men who were supposed to be working for him. The killing is often mentioned in company histories, possibly because John McLoughlin Sr. was an influential employee, if rather bitter after his son died.

After the murder, there were many questions about who did it, and whether the guilty parties ever paid for their crime in any way. This has all the makings of a good murder mystery, more than 170 years after McLoughlin met his untimely end.

At the time, there was no formal autopsy, no charges laid and no conviction.

Author Debra Komar, a practising forensic anthropologist, has worked through a vast array of historical materials to piece together a fresh look at the murder. She has done more to solve it than anyone else has in the many decades since McLoughlin died.

Relying on Hudson’s Bay Company reports, correspondence and other sources, she has put together a compelling case that is highly entertaining. She takes us back to that miserable place, on a miserable night that turned rather ugly.

But then, life at the fort had been ugly for some time. It was not a pleasant place, with a volatile mix of people who seemed to be coming apart at the seams. McLoughlin, the victim, was clearly out of his depth as the person in charge, and comes across as a difficult man to like.

Murder is never right, but it’s easy to understand why someone decided, thanks to a mixture of alcohol and rage, to do the killing.

As the story unfolds, Komar gives the reader a sense of what life was like in Hudson’s Bay Company forts. She deals with some of the people who helped shape the company, and the internal politics that led to decisions and assignments that were not always the best ones.

Given that the company’s network of fur-trading posts, and its relations with indigenous peoples, were crucial to the European settlement of British Columbia, it is good to have a better understanding of how it operated.

To be fair, not all forts were as bad as Stikine, which contained the dregs of the company’s workforce.

It was an assignment of last resort, a place where people went because they had nowhere else to go. That kind of place demanded a firm, fair leader, but in McLoughlin, it did not have that leader.

Fort Stikine was established by James Douglas in 1839, a few years before he set up a fort on the southern tip of Vancouver Island, and helped create Victoria.

There are many other Victoria connections in this book, most notably Roderick Finlayson, who had been McLoughlin’s assistant before coming to Victoria to help build the company’s new fort.

The Bastard of Fort Stikine is a fine tale, and Komar has done a superb bit of detective work in gathering the evidence and sorting out what happened the night McLoughlin was murdered.

Even after all of these years, some secrets are out, and it makes for fascinating reading.

The reviewer is the editor-in-chief of the Times Colonist.