From the rocky shores of Becher Bay near Metchosin, the Pacific Ocean may appear cold and forbidding, but the Sci’anew First Nation and Trust for Sustainable Development Inc. are musing whether it has the energy to heat a new community development.

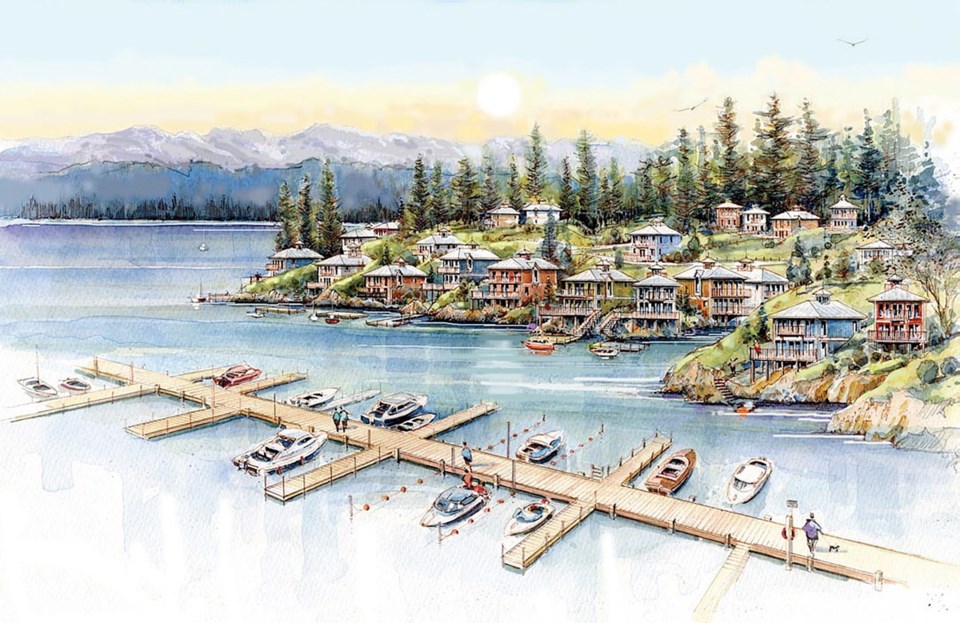

The trust and Sci’anew, also known as Cheanuh, are partners in a new town development called Spirit Bay, where they are proposing to build a thermal energy plant that would use a heat-exchange system to harvest some of the solar energy absorbed by the ocean to supply a district-heating system.

“When you talk about heat, you tend to think of hot things,” said David Butterfield, co-founder of the Trust for Sustainable Development. “But it’s just energy, and there is a huge amount of energy in water, even at 10 C.”

Similar to urban district-heating systems that tap the waste heat from sanitary sewer systems installed in developments around Metro Vancouver, the thermal energy system being proposed for Spirit Bay would use a radiator-like heat exchanger.

Except instead of being placed alongside warm sewer pipes to exploit the difference in temperature between warm water and colder water, Spirit Bay’s would be placed in the ocean alongside Cheanuh Marina in the bay to do the same thing. “It’s like a reverse refrigerator,” Butterfield said. “You take a degree or two out of a lot of [sea water] to produce many degrees of rise in temperature in a smaller amount of water.”

That heated water would be piped directly to the homes and buildings of the Spirit Bay development with the piping system to be installed at the same time as other infrastructure. Heat pumps in each building would extract the energy for domestic heating and the water would be recirculated through the system.

Earlier this month, the Cheanuh were awarded $40,000 by the provincial government’s First Nations Clean Energy Business Fund, which is aimed at promoting First Nation participation in the clean energy sector, so the community could study the proposal.

In making the award Dec. 10, John Rustad, minister of aboriginal relations and reconciliation, called the Cheanuh “forerunners in B.C.” who are working on using new renewable sources of energy.

Such heat-exchange systems are no longer new. In Metro Vancouver, the 2010 Olympic Village development, now known as The Village on False Creek, was an early adopter of heat recovery from sewer systems. Companies such as Burnaby-based International Wastewater Systems are installing them in condominium and commercial developments in North Vancouver, Richmond, Vancouver and other municipalities.

As for ocean-based heat exchange systems, the Alaska SeaLife Center installed a $833,300 plant at its aquarium in Seward, which saves it from burning $192,000 worth of heating oil and cuts its carbon dioxide emissions by 590 tonnes, according to a 2013 presentation produced for a clean energy conference.

Butterfield said the $40,000 grant will be used to defray the cost of engineering studies that the Cheanuh and the Trust need to do to evaluate vendors and to pick a location for the exchanger, but they are committed to the concept, which is priced into the development.

The Trust is already selling homes, starting at $259,000, in the first phase of the development. The district-heating system accounts for $20,000 of the price. Buyers will also pay ongoing utility costs, which also offer the Cheanuh an additional revenue stream, but Butterfield said the bills will be less than for equivalent electric or natural gas heating.

Overall, Spirit Bay’s first phase will consist of a town centre with shops, offices, a resort and spa with 800 homes on 16 hectares. In total, the Cheanuh hold about 400 hectares of south-facing waterfront land on the bay, which Butterfield said could take 100 years to build out.

“They’re looking to create a sustainable way of growing and creating jobs and economic opportunities,” he said.

Cheanuh Chief Russell Chipps said that his people have always relied on the ocean for sustenance through fishing and gathering shell fish.

“It only makes sense to us now that we are looking to be a net generator of energy using thermal energy from the ocean to heat Spirit Bay,” he said.