JAMES KWANTES

Vancouver Sun

Apple’s new spaceship-style headquarters in Cupertino, California, will be a four-storey showcase of green design featuring curved glass and apple orchards in the large outdoor courtyard.

It’s being built using sand and gravel from a quarry at the northern tip of Vancouver Island.

The Apple campus is one of several landmark structures in the San Francisco area constructed using material from the Orca quarry west of Port McNeill, which is run by Vancouver-based Polaris Minerals.

“One of the treats about the aggregate industry is that you actually get to see where your products go, unlike gold, where it just disappears into this opaque market,” company founder Marco Romero said in an interview at his Vancouver office.

Polaris products were also used for the new San Francisco-Oakland Bay Bridge (which displaced Vancouver’s Port Mann as the world’s widest), a seismic retrofit of the Golden Gate Bridge and San Francisco’s Millennium tower, one of the tallest residential buildings west of the Mississippi.

Since the quarry opened in 2007, the company has become a premier supplier of high-quality sand and gravel for concrete used in California markets. The company also ships sand to Hawaii, where laws ban the use of beach sand for concrete.

“We love saying, ‘We sell sand in Hawaii,’ ” Romero said with a chuckle.

Polaris, listed on the Toronto Stock Exchange, is one of three B.C. Export Awards finalists in the natural resources category. The awards are being handed out today in Vancouver.

In a province where mining companies sometimes clash with First Nations deeply rooted to the land and water, Polaris has not only avoided conflict but built strong relationships.

Romero reached out to local First Nations in 2000 immediately after identifying the property. Little by little, a dialogue began and trust was established. It wasn’t always easy, he said.

“Their history with our society has been very bad. We have historically mistreated these people, these communities. It was very difficult to earn trust.”

Romero’s early efforts — combined with years of relationship-building — set the stage for the current partnership. The ’Namgis First Nation owns a 12 per cent equity interest in the quarry, and Polaris has an impacts and benefits agreement with the Kwakiutl. About half of the quarry’s employees are First Nations people.

“The First Nations weren’t on the outside being consulted, ‘dealt with,’ ” said Romero, who stepped down as chief executive in 2008, but remains a Polaris director. “They were really part of the project, part of the evaluation, planning, development and now the operation, in the case of Orca quarry.

“They forced us to accept high standards because they wouldn’t accept anything less.”

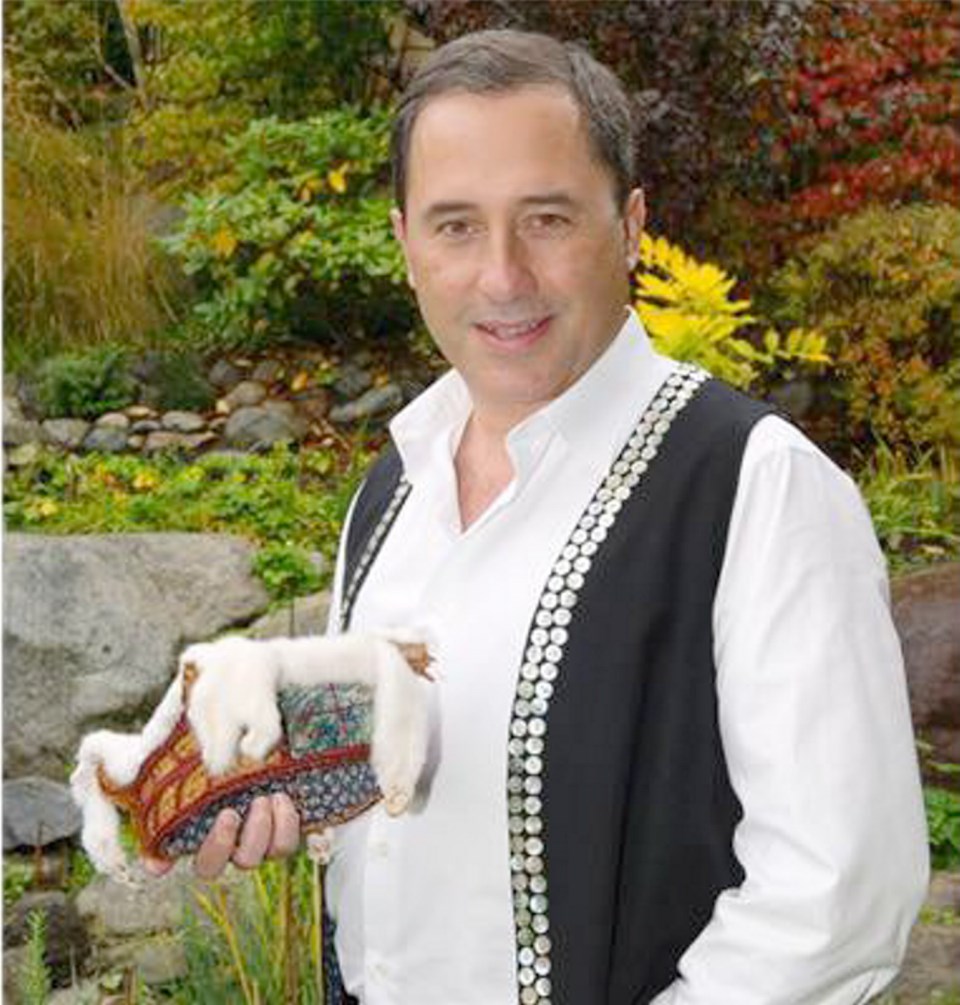

Spend some time in Romero’s office and it becomes clear that his First Nations connections run deep. The walls are covered with native masks and artwork from his personal collection, and one of the framed First Nations prints was made by a native artist who works at Orca. More significantly, Romero has been formally adopted into the families of two hereditary chiefs of different Island First Nations.

It’s been quite a ride for the father of five, a globe-trotting resource entrepreneur who was born in Chile to Spanish parents and grew up in Montreal. Romero has worked in more than 40 countries and is one of the co-founders of Eldorado Gold, which grew out of Romero’s private company Eldorado Ventures Inc. and is now one of Canada’s largest gold miners.

He’s also worked with some of the heavyweights of the global mining industry, including mining financiers Robert Friedland and Ned Goodman. In 1991, Romero cold-called Friedland from Beijing while looking for funding for a gold project in Czechoslovakia after his partner pulled out.

“I was in Beijing, had just come out of Mongolia, and I got word that my partner had dropped me,” he said. “I didn’t want to lose this deposit. I spent a thousand bucks one night on phone calls from a hotel in Beijing. It was before cellphones.

“I called him up cold, did a deal, but later lost the project [to mining giant Rio Tinto].”

Romero later worked with Friedland at the original Ivanhoe Mines before founding Polaris so he could work closer to his family.

He keeps a hand in gold as president and CEO of Delta Gold, which is developing the Imperial gold project in southeastern California, acquired from Goldcorp. Delta recently agreed to merge with Commonwealth Silver and Gold, which is advancing a gold-silver project in Arizona.

Romero took Delta Gold public in February 2013 at the start of one of the worst junior mining bear markets in recent times.

It was a familiar experience — the Orca quarry’s first product was shipped in the spring of 2007, a year before the financial crisis sparked America’s worst recession since the Great Depression. Demand for construction aggregates went off a cliff, dropping 65 per cent in the company’s primary California market.

“Within a year — bam! — the bottom fell out. It was shocking,” he said.

The company kept the quarry operating even as it lost money.

“We never wanted to lose our customers. We never wanted to be seen as the company that wasn’t reliable,” he said.

“We believed in what we were doing. We never doubted our long-term plan. We knew it had to come back, and it’s coming back strong now.”

Polaris now ships almost as much material in a single quarter as it did during the entire year at the peak of the recession.

“When I look back now, I can see that our plan wasn’t derailed. It was delayed.”

Orca is now the largest sand and gravel quarry in Canada and its product is highly valued for its strength and durability.

As mining operations go, the business has a fairly low environmental impact. Sand and gravel is loaded by conveyor directly onto Panamax ships, which each transport 72,000 metric tonnes of material — equivalent to about 2,500 dump-truck loads. The amount of waste rock is much lower than mines that produce gold, copper or any other commodity.

“We actually ship 97 per cent of what we touch,” Romero said.

Polaris is as much about transportation and logistics as it is about digging up rock — the off-loading at the San Francisco port terminal it owns is highly automated.

The company is also building a port terminal in Long Beach, which will open up the fast-growing Los Angeles market just as the Southern California economy picks up, with a corresponding increase in multi-family residential, corporate construction and seismic upgrades. Construction is expected to finish by year’s end.

Polaris also owns the Eagle Rock granite quarry south of Port Alberni, which is permitted but isn’t operating because its granite is used for less-in-demand asphalt.