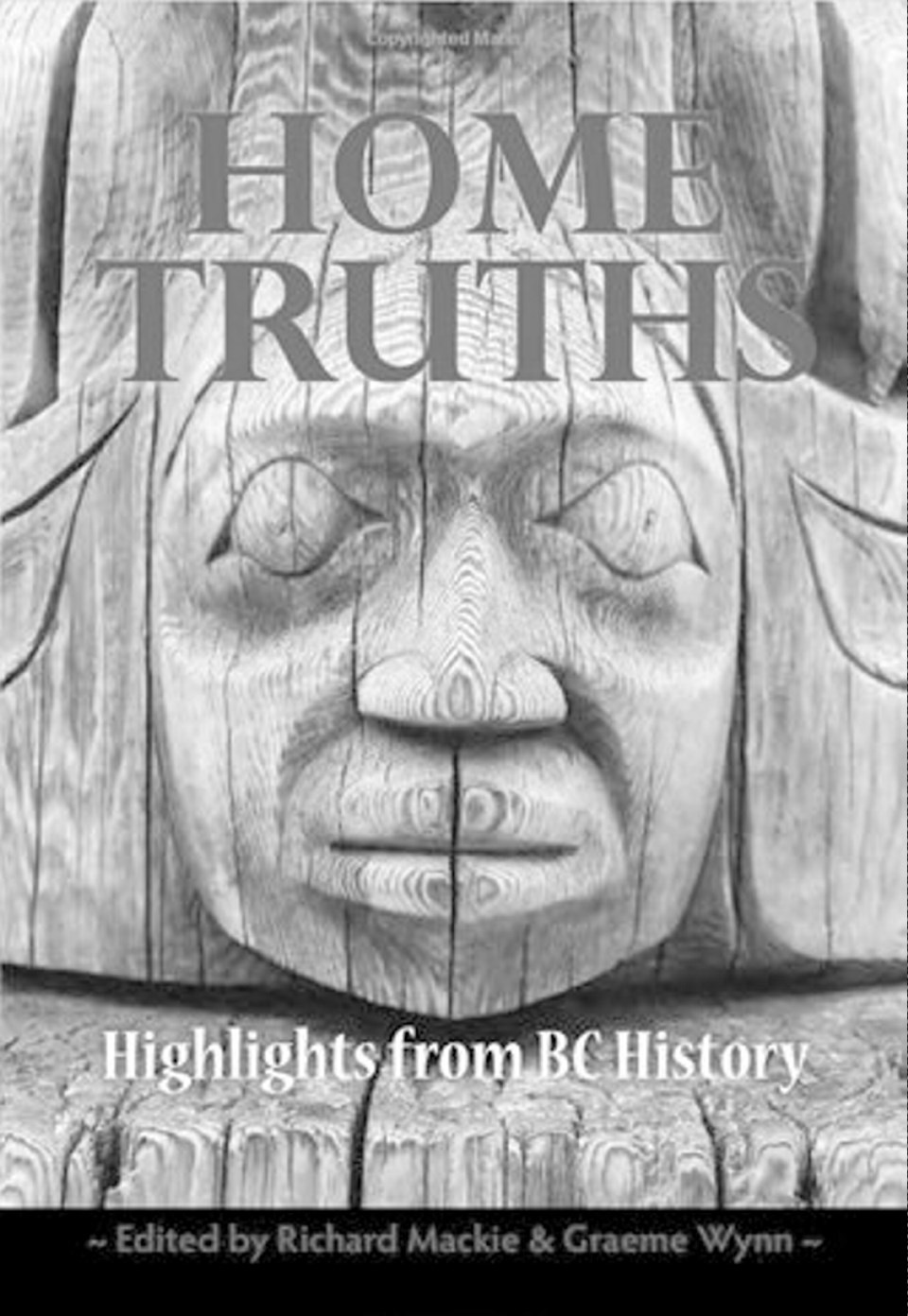

Home Truths: Highlights from B.C. History

Edited by Richard Mackie and Graeme Wynn

Harbour, 416 pp., $26.95

Home is where we find it, home is what we make it. Home can mean something different to everyone, yet we all know the value of having a home, and feeling at home where we are.

Home, as they say, is where the heart is.

The concept of home is the central theme of Home Truths, a collection of some of the best writing from 40 years of B.C. Studies, a fine scholarly journal dedicated to the history of this province. It could not have been an easy task, since the journal has published more than 600 pieces since 1968.

Editors Richard Mackie and Graeme Wynn have gathered 11 essays that cover the various meanings of home. They were written by leading historians and authors, people such as Jean Barman, George Bowering and Patrick Dunae.

It would be hard to escape the cold reality contained in these pages — that for most British Columbians, home is something we can take for granted because others were deprived of their homes. This happened time and time again, in urban areas such as Victoria and Vancouver as well as in rural areas such as Pennask Lake, west of Kelowna.

The indigenous peoples who had lived here for centuries were shunted aside, apparently because their needs were not as important as the needs of the incoming settlers. They were forced onto reserves, and then later, when many of the reserves were deemed to have value, they were forced to move again.

That this happened in British Columbia is hardly news; we have been dealing with the consequences for decades.

A book such as this, one that celebrates the value of having a home, helps remind us of the way European settlement shattered any sense of home that might have been felt before the Europeans arrived. The rights of the indigenous peoples to the land where they had been living — their homes — were ignored in the name of progress.

A closer look at history can also bring a reconsideration of what we have believed. As Dunae has shown through extensive research, for example, Victoria’s Chinatown was not the only place where Chinese-speaking people lived, and it was not strictly made up of people from China. It was more of a centre of Chinese activity, a home base for an extensive community.

Home Truths also deals with settlements based on utopian ideals or, failing that, misinformed enthusiasm. The book takes us back to the days of logging camps, where men worked long hours with miserable living conditions. It examines the homes for the aged over the years, and the way society treated the elderly.

There are occasional treasures that help to bring a smile. One example is a homestead map of the Boston Bar region of the Fraser Canyon, which was not exactly the kind of terrain suitable for dividing into 160-acre chunks. But there can be no question that it looks good on paper.

In the end, does this book matter? Well, yes. As the authors state in their introduction, it’s important for us to “move forward in ways that ensure justice, dignity and appropriate opportunity for all British Columbians.”

It has not always been that way, and even today, it’s not always easy. But it’s a goal worth striving for.

B.C. history, in itself, can be a fascinating topic. But there is little benefit in learning about history if we are not willing to learn from it as well. And that point is made abundantly clear in Home Truths.

The reviewer, the editor-in-chief of the Times Colonist, has written extensively on B.C. history.