The following is an excerpt from The Library Book: A History of Service to British Columbia, written by Times Colonist acting editor-in-chief Dave Obee.

The Library Book placed third in this year's Lieutenant-Governor's Medal for Historical Writing Competition. Lt.-Gov. Steven Point will present the awards this week at the B.C. Historical Federation conference in Campbell River.

All John Maitland Marshall wanted to do was help people get books from Victoria's new bookmobile. But in 1954, he found himself at the centre of a major controversy and a victim of the Red Scare that reached into Canada and its libraries.

Marshall was fired two months after he was hired, before the mobile service even hit the road. He lost his job because of his past.

Before he came to British Columbia, he had been connected with groups that leaned to the political left. By the time things cooled down, there were calls for book-burning parties, Marshall had left the province and qualified librarians were boycotting the Victoria Public Library.

It was the McCarthy era. Fears of the Communist threat swept through North America, sparked by United States senator Joseph McCarthy's hunt for Communists in positions of authority. Freedom of speech and association were under attack.

Marshall, the son of a banker, was born in Saskatchewan in 1919. He and his wife, Christine Smith, had two small children, John and Kathleen. He had been the children's librarian for the Fraser Valley Regional Library for

18 months before he was hired in Victoria in December 1953.

Marshall did not seek the Victoria job; he was asked twice to apply before he agreed. There had been no complaints about his work and he was certainly well prepared for it, with a Master's in English from the University of Saskatchewan and a Bachelor of Library Science degree, with honours, from the University of Toronto.

But his qualifications or the mouths he had to feed did not matter to the Victoria library board. What mattered was that "a group of public-spirited citizens," as the board put it, had uncovered some dirt in his past.

Marshall had been educational director of the People's Educational Co-op in Winnipeg in 1947 and spent six months as assistant editor of the Westerner, a leftist paper. He had attended the Canadian Peace Congress in Toronto in 1949, 1950 and 1951 and the congress, many believed, was a Communist front.

Because of that, Marshall was fired. He learned of his dismissal when it was reported in the Victoria Daily Times.

Marshall appealed the firing, saying that he was not, and never had been, a card-carrying member of the Labour Progressive Party, which had been linked to the Communists. He said that he had ceased any public connection with political matters when he decided to become a professional librarian.

He also took aim at the "public-spirited citizens" who had accused him. "Groups or individuals which carry on secret investigations into a man's beliefs and past associations, and put pressure on his employers to fire a fully qualified employee without giving him the opportunity to defend himself, are undermining our democratic freedoms," he said.

One library board member told the Daily Colonist it was good the Marshall matter had been made public. "If they are labelled, they are useless to the party," the unidentified member said. "We should always be on the watch for them."

The board ordered a review to find and remove "subversive pro-Communist" books from the library, and Victoria Mayor Claude Harrison declared that he would support the burning of any subversive literature in the library.

"It's very easy to see which is Communist literature," he said. "And I know what I would do with them throw them in my furnace."

Ald. Brent Murdoch said any seditious or subversive books should be removed "and any member of the library staff who belongs to a Communist organization will go out behind the books." It was time, he said, to clean up libraries.

The comments of Harrison and Murdoch sparked a huge outcry, with supporters lining up on both sides.

Premier W.A.C. Bennett said that book-burning would be "a bunch of foolishness," and threw his support behind Marshall. "I am 100 per cent opposed to what people call McCarthyism and witch-hunting."

Marshall had several other defenders. Roderick Haig-Brown of Campbell River, a magistrate and one of Canada's best-known authors, said Harrison was "dim-witted" and "not very thoughtful, nor intelligent."

Saanich Reeve Joseph Casey said Marshall should get a hearing, adding that if subversive books were to be taken from the library shelves, Mutiny on the Bounty would have to go.

But the anti-Communist fervour was widespread. Victoria MLA Lydia Arsens, for example, said that removing all books about Communism and by Communists would not "be denying any citizens freedom."

The Daily Colonist weighed in. "Unless McCarthyism is to raise its ugly head in Canada, something better than hearsay will be required to support assertions of subversive literature on the shelves of the Victoria Public Library," it said.

"There have been no bonfires of books in this land, no edicts such as Hitler's or Stalin's that one book or another must be consigned to the flames. Good taste on the part of the public in selecting its reading, and maturity of thought in perusing it have proved far more effective than any form of censorship."

The Victoria Daily Times called for common sense and quiet analysis. "No honest Canadian wants the library to become a propaganda agency for Communism," it said. "On the other hand, no thinking people want excitement over such a possibility to restrict desirable library service or to eliminate from circulation books, magazines or journals which throw informative light on the activities of those interests that swear allegiance to Moscow."

It noted the library board's position was that its role was to provide as much material as it could on as many subjects as possible within the law and to trust readers to form intelligent conclusions. "We believe that is the right attitude."

The Vancouver Sun said it hoped the "stupidity of those responsible" for the talk of

burning books would give way

to enlightenment.

The library's staff association defended Marshall, saying the board should explain why he had been fired. "Never before in this library has an individual, whether temporary or permanent employee, been dismissed without reason," the association said. It argued that Marshall was competent and enthusiastic, and said that private individuals had the right to freedom of thought, "one of the principles upon which a library is founded."

Marshall was fired with only a few days left in the library board's annual term. He was given a chance to argue his case before the new board the following week.

One of the new members was Robert Wallace, a Victoria College mathematics professor, who said he was amazed by the idea of removing books. "Libraries are the greatest single contributing factor to education in its broadest sense."

Marshall pulled no punches. "I challenge the board to produce any proof that I have, since becoming a librarian, abused my position in any way, or allowed my opinions whatever they might be on matters outside the profession to influence me in any direction in the performance of my professional duties," he said.

"It might be held that because of what I am or what I believe, I may in some way abuse my position in the future. This assumption comes dangerously close to justifying, on the part of employers, an attempt to enquire into the political, social or economic beliefs and in the religious principles of an employee.

"No employer has any such right in a democratic country."

Marshall's plea failed; with only Wallace speaking in his defence, his firing was confirmed in a three-one vote. Chief librarian Thressa Pollock resigned in protest.

The B.C. Library Association held a special meeting in Vancouver to discuss the Marshall case. More than 100 members attended. The group wrote a letter of recommendation for Marshall and urged its members to refuse positions in Victoria until a new library board was in place.

"Can or should a member of the BCLA apply for any position in the Victoria Public Library as long as the policy of the board remains what it is?" the association's publication, the Bulletin noted. "It is in the answer to this question that the association's real attitude toward witch-hunting may be made known. Let us hope we have the conscience and courage to say 'no.'"

By May 1954, six of the 11 full-time professional librarians at the library had resigned and the library had not been able to replace any of them. Georgina Wilson, the acting head of the circulation department who resigned so she could marry, used her letter of resignation to plea "that the present board support the principles of tolerance, intellectual freedom and high standards of service that were characteristic of early and excellent boards."

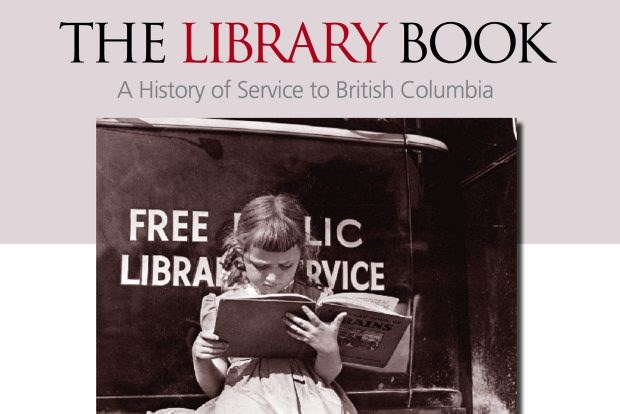

Nora Dryburgh, who had been appointed to replace Marshall, was among those who resigned. Her departure meant the bookmobile service had three librarians before it delivered a single book to Victoria's suburbs.

After his firing, Marshall took his family wife Christine, one-year-old Kathleen and five-year-old John to Yorkton, Sask., where he got a job with the rural school library service. After four years there, he spent two years as the first professional librarian in Kitimat, and then moved to Toronto to become the head librarian at a new branch in North York.

He capped his career by spending 17 years teaching in the faculty of library science at the University of Toronto. He loved books, and loved reading books about books. He also edited Citizen Participation in Library Decision-Making: The Toronto Experience, which was published in 1984.

The Victoria library paid a heavy price for the Marshall affair. It had trouble attracting qualified librarians until the board members involved in the firing were gone. John C. Lort, hired to replace Pollock as the head librarian, spent several years restoring the library's stature in Victoria and in the library community.

In 1998, the board of the Greater Victoria Public Library apologized to Marshall, flying him and his wife to Victoria so he could receive the apology in person. "What goes around, comes around," Marshall said at the ceremony. "So be it."

Neil Williams, the library board chairman, told Marshall that the events that had happened would have been unjust at any time. "The fact that they took place within a library, in my mind, pushes them over the border into obscenity."

Robert Wallace, the former board member who had argued on Marshall's behalf, expressed regret that he had not been able to convince the others.

And with that, as Marshall's son, Dr. John Marshall, said later, "the dark cloud over his career was finally lifted."

The B.C. Library Association gave a plaque to Marshall. It also renamed the association's intellectual freedom award in his honour.

Marshall died in Toronto on Oct. 26, 2005. His obituary, written by his family, described him as "a passionate bibliophile and ardent supporter of social justice."