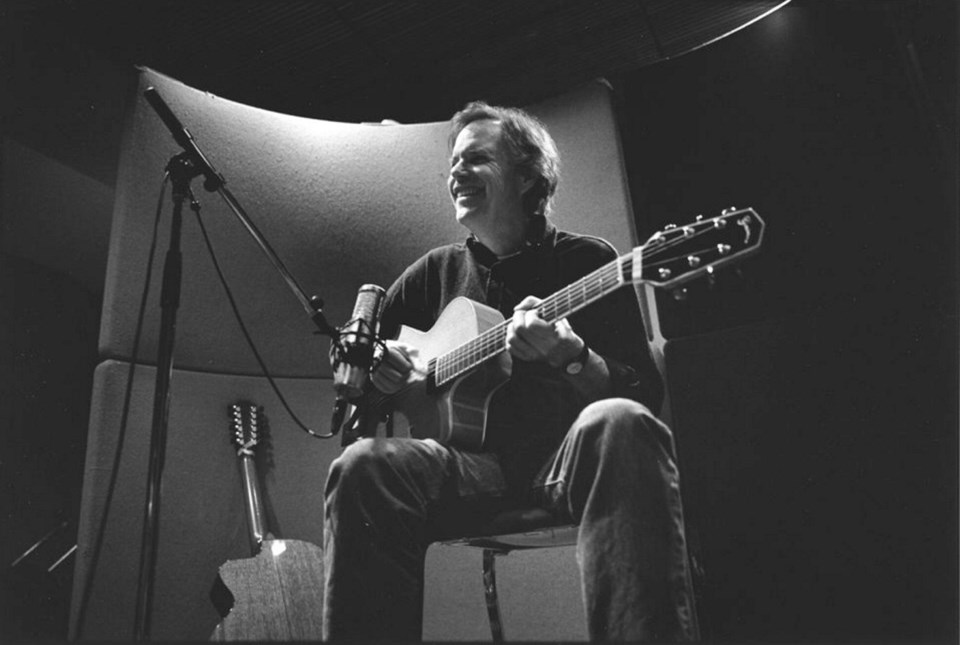

Leo Kottke

When: Friday, 8 p.m. (doors at 7:30)

Where: Alix Goolden Performance Hall (907 Pandora Ave.); also performs Saturday in Courtenay at Native Sons Hall and Sunday on Saltspring Island at Artspring Theatre

Tickets: $35 at rmts.bc.ca; $40 at the door

Celebrated guitarist Leo Kottke lived in a dozen states growing up, including Georgia (where he was born), Oklahoma (where he was raised) and Minnesota (where he currently lives).

On a certain level, he has taken each state to heart, infusing his songs with details specific to his experience. But of all the places he has called home, there’s a lure to Minnesota that Kottke can’t shake.

At first, he decided to live in Minnetonka, a suburb of Minneapolis, because it’s where his dad grew up and where his grandfather worked.

“I would hear about this area and see it almost every year when my folks had some vacation time,” Kottke said this week in an interview from his home.

“We’d spend a week or two here. It was the one constant when I was growing up. When I got out of the navy, I came back. The navy was dissociative all on its own, so I went to Minneapolis for the continuity.”

Kottke was unusual in that he enjoyed moving around as a child. The lure of a new city, and what adventures he would discover, was a constant source of excitement in his ever-changing world, he recalled.

“I can’t remember a time when I was more bereft for the friends I was leaving than I was happy for the unknown I was heading to. I’m not sure why it worked that way, because it was the opposite of the usual. But it did.”

Integral to his career as a musician was time he spent living with his family in a suburb of Washington, D.C. Kottke was a music nut as a teenager, having taught himself the guitar at age 11. At the time, the older brother of a neighbour Kottke was friendly with had an impressive record collection full of stringband groups, which came in handy when Whippoorwill Lake and Watermelon Park, a pair of folk-leaning Virginia music festivals, came into being in the early 1960s.

Kottke headed there with his friends in search of inspiration. What he found soon after arriving were unparalleled musical environments homespun in their tone and approach.

“For two days, the only people playing on a stage were amateurs. That was a trip. There was some outstanding playing going on there, and it showed you what’s possible. It also showed you attitude, which is probably the most important thing. It’s like learning your manners, but it has to do with playing. I didn’t know I was getting that. I thought I was just getting drunk on everybody else’s beer, and hearing some fun stuff. I learned how to behave on a fretboard. That was a great gift.”

Kottke is the proud owner of an askew world view. A former English major at Minnesota’s St. Cloud State University, he is undoubtedly intelligent. However, that alone is not what makes him such a curiosity to some and a much-adored musical magician to others. His virtuosic ability with a guitar has inspired a legion of fans, beginning with his debut, 1969’s 12-String Blues, a live album recorded at a Minneapolis coffee shop.

The music, largely his own, was only half of the appeal. In an era of über-serious artistes, his self-deprecating liner notes on 12-String Blues — in spite of his obvious and considerable talent — was a welcome relief (for example, by way of explaining his song The Prodigal Grave, Kottke wrote: “This was written in a fit of terror while trying to calm down. It originally contained many more verses which later served only to confuse, so they were discarded.”)

He has become, in the years since, a performer of much renown, in part due to his between-song monologues. During his previous Victoria concert, in 2011, he was in fine form on that front. When he returns to Alix Goolden Performance Hall on Friday, the first of three Vancouver Island concerts this week, it would be unusual if he didn’t talk at length about his life.

“I can’t do it unless I’m on stage, and I only do it on stage because I don’t know what to play next,” he said of his in-concert chatting.

But the music means more to Kottke than his reputation as a raconteur. In fact, he worries sometimes that his storytelling overshadows his guitar playing. Kottke once had a conversation about this with John Hiatt, a performer whose remarkable touch with a song is matched by his ability to tell a great story. They both agreed that music should win out every time, Kottke said.

“John was — and is — maybe the funniest musician I’ve ever heard, and musicians tend to be funny. But one time I ran into John, and he wasn’t saying much [on stage], so I asked him what happened. And he said. ‘Aw, who wants to be a comedian?’ I liked that.”

Kottke remains a master conversationalist despite his apprehension.

He said he once took to fixing car engines as a way of keeping both his hands and mind free from rust. His recordings have been sporadic in recent years — 2005’s Sixty Six Steps, his collaboration with Mike Gordon of Phish, was his last studio effort — so adopting new ways of learning is how he stays fresh.

“That was amazing for my hands,” he said of his car care days. “They got a little burned, a little sawed, a little cut, a little crushed, but nothing that didn’t pass. I get the engines apart, and then I’d supe it all and rebuild it. The contortions you get into are what worry you, more than the blows or the injuries.”

But what about his hands, the most important tools of the guitar trade?

“Well, I noticed that my hands felt like boots. The fingers were gone. It scared me, so I ran into the house and grabbed a guitar, and the playing was like nothing I’ve ever experienced. There’s a thing about tone production, about not having any wasted movement. Usually, you learn it by way of geometry. But I can tell you that if you use all of the other muscles in your hands that are neglected when you’re playing guitar, and get them as up and as operative as your guitar muscles are, you’ve really got something.”